2

They Did Not Deny Us

Arakan, ancestral homeland and recognition of the Rohingya community

“The name of an ethnic group is whatever they call themselves. We didn’t become Rohingya because someone from another country wrote it in a book. We are born in the land named Rohang (Arakan) and we are inhabitants of Rohang, therefore we call ourselves Rohingya.

“Those names written by people from other communities were written as what he saw, heard in his ears and understood. But even then, they did not deny us.”

Aman Ullah, Rohingya elder

2023

Today, the Rakhine Buddhist and Rohingya Muslim communities both draw their pasts to the shared historical homeland of Arakan (Rakhine State today). Unfortunately, successive Burmese regimes, along with many communities in Myanmar, have labeled the Rohingya foreigners, and have denied they belong to the country.

From the 1600s to the early 1800s, missionaries, European explorers, trading companies and early diplomatic missions wrote of the Muslim community in Arakan. References to the Rohingya predate British occupation and colonization of Burma, which began in 1824 and lasted 124 years. The British introduced highly racialized systems of record keeping; a policy of open borders between British India and Burma meanwhile resulted in the mass migration of people between the two territories. Yet even then, reports, censuses and other correspondence of that time describe the long-settled Muslim community in Arakan as indigenous to Burma. In the fourteen years after Burma’s independence in 1948, a vibrant press consisting of daily, privately owned newspapers reported on Arakan, the Rohingya community and Rohingya involvement in Burma’s political life, as well as their place within the collective identity of the nation.

A collection of old journals, rare manuscripts, books, surveys, censuses, newspapers and other forms of correspondence dating back over 200 years trace the ancestry of the Rohingya community. They acknowledge Rohingya identity. They show how others recognized the Rohingya within the diverse makeup of Burma at the time, and they chronicle the troubled histories of Buddhist and Muslim communities who then and now proudly claim Arakan as their ancestral homeland.

1653

Sebastian Manrique: Itinerary of the Oriental Missions of Father Manrique - Chapter 10: Of How I Left Bengal for the Kingdoms of Arakan

Sebastian Manrique was an Augustin missionary from Portugal. He traveled through the East from 1629-1643, including Arakan (which he wrote as Arracan). In 1653, his book, Itinerary of the Oriental Missions of Father Manrique, was published. In the book, he writes about Muslims in Arakan, including some in the royal court. He also describes Muslims brought from Bengal to Arakan as captives and slaves.

1676

Wouter Schoutens book: Wouter Schoutens Travels Into The East Indies and one of several engravings of Arakan.

Wouter Schoutens was a Dutch surgeon. He traveled to the Dutch East Indies for several years. He visited Arakan from 1660-1661. His book, Wouter Schoutens Travels Into The East Indies, was published in 1676. Drawings and observations describe the people of Arrakan and the presence of Muslims in Arakan at the time..

1738

Chapter 3: Superstition, Temples, Priests, Sacred Ceremonies, Christian and Mohammedan Religion in this Kingdom

Thomas Salmon’s The Present State of All the Counties and Peoples of the World. Seen is the Italian edition printed in 1738 and an engraving depicting the way inhabitants of Arakan dressed.

Thomas Salmon was an English historian. In 1738 he published The Present State of All the Countries and Peoples of the World. It included a volume titled, Present State of the Kingdom of Arrakan, about the people of Arakan, including the Muslim community at the time.

“Arakan was never a territory or region or country with one people. It was always a multicultural, multilingual place.”

Nurul Islam, Rohingya elder

2022

1777

“Almost three fourths of the inhabitants of Rekheng (Arakan), are said to be natives of Bengal, or descendants of such…”

(June 1777)

The trade of slaves from Bengal into Arakan in the 17th and early 18th centuries increased the Muslim population in Arakan. An anonymous account by a British civil servant in June 1777 describes a large group of people taken captive from Bengal and brought to Arakan (or Rekheng) to be sold as slaves. It also describes how large the Muslim population was in Arakan at that time.

1795

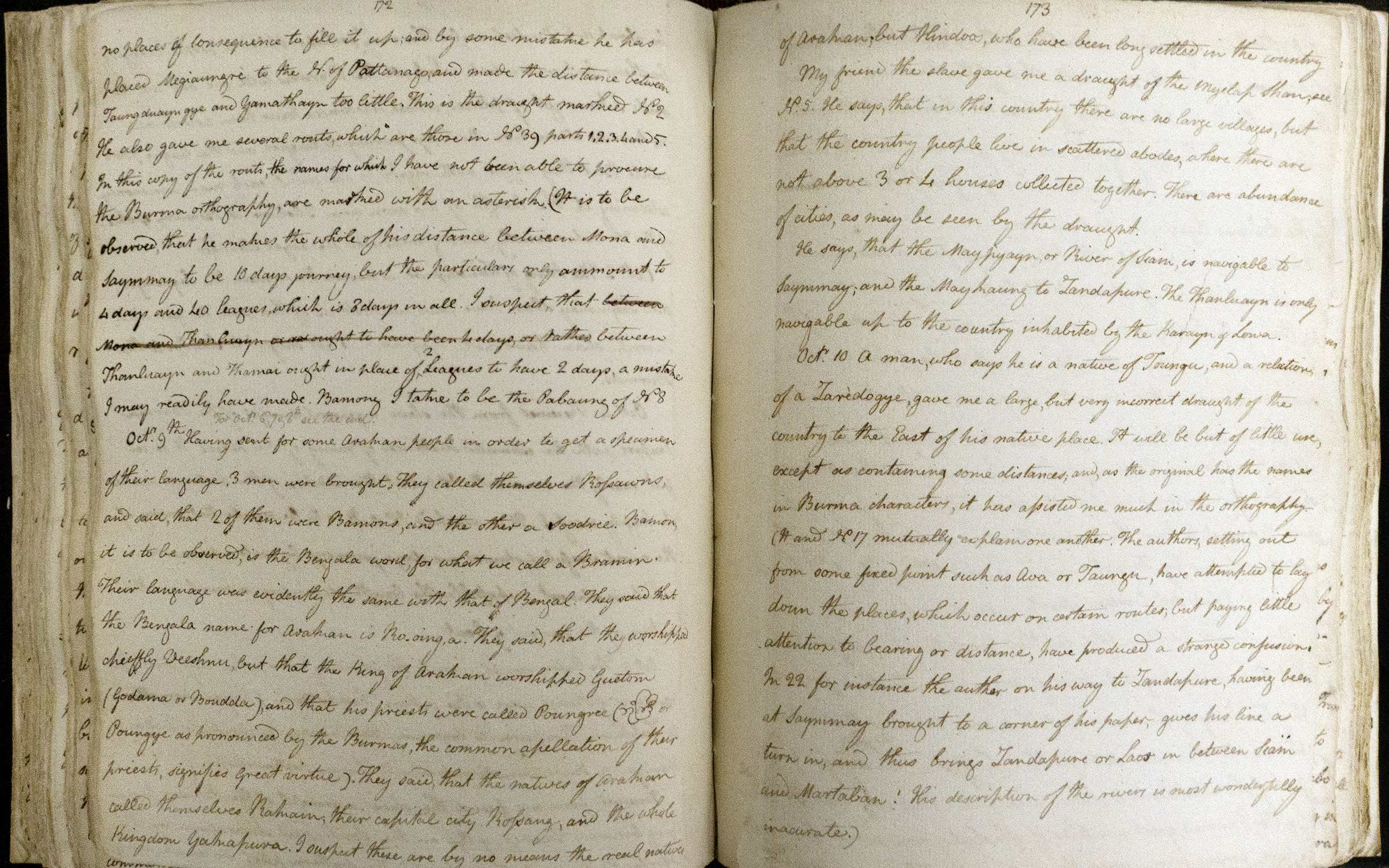

MSS EUR C12

Francis Buchanan M.D. was a doctor and a botanist. He served with the British East India Company. In 1795, he traveled to Burma as part of a diplomatic mission. He wrote extensively about the people he met on this journey, including their languages. Buchanan did not travel to Arakan, but in his journals are some of the first documented references to the Ro.oinga community and their language. He wrote about and recognized the existence of Buddhist, Hindu and Muslim communities living in Arakan. In 1799, Buchanan published some of his findings in the journal, Asiatic Researches. The article details several languages of Burma, including the Rooinga.

1795

Their language was evidently the same with that of Bengal. They said that the Bengala name for Arakan is Ro.oinga.

Francis Buchanan, 1795 (p 172)

One of several copies of Buchanan’s journals and writings from his time in Burma.

British Library IOR/L/PS/19/13

1799

An original printing of Buchanan’s article published in the journal, Asiatic Researches (1799)

A COMPARATIVE VOCABULARY

OF SOME OF THE LANGUAGES SPOKEN IN THE BURMA EMPIRE

Francis Buchanan, M.D., 1799

Asiatic Researches 5 (p 219-240)

The Mahommedans settled at Arakan, call the country Rovingaw…

I shall now add three dialects, spoken in the Burma empire, but evidently derived from the language of the Hindu nation.

The first is that spoken by the Mohammedans, who have been long settled in Arakan, and who call themselves Rooinga, or natives of Arakan.

1799

1801

..when impelled by Acts of oppression and cruelty in their own country, from twenty to thirty thousand of these unfortunate People claimed the protection of the Company.

1801 (p 6)

Communications from the British East India Company document the situation for refugees fleeing from Arakan into Bengal, like these from March 1, 1799 and March 20, 1801.

IOR/F/4/128/2381

In 1784, the Burmese empire invaded and occupied Arakan. Prior to this time, Arakan was a separate kingdom. Over the following decades, Buddhists and Muslims from Arakan were oppressed by the Burmese occupiers. Tens of thousands of Buddhist and Muslim refugees (emigrants) fled Arracan across the Naf River into the British controlled area of Chittagong in Bengal to escape persecution. In 1824, Britain declared war on the Burmese empire. Arakan was annexed into British India in 1826.

“It is said in Arakan, the Rakhine and the Rohingya were brothers. Two races from the same place. One believes in Buddhism and one believes in Islam. We Rohingya were here since long before 1823. Our fathers, grandfathers, great grandfathers, children and grandchildren were all born here.”

Mohammed Hussein, Rohingya elder

2018

1826

Adriano Balbi’s Atlas Ethnographique Du Globe Ou Classification Des Peuples Anciens Et Modernes D'Apres Leurs Langues, published in 1826.

Adriano Balbi was an Italian geographer. In 1826, he published one of the first ‘linguistic atlases’. It detailed the languages of the world. It was printed in Paris. The Rooinga language is included in the Asian languages section with translations of specific words. A footnote in the atlas (#69) provides more context and history about the community.

1826

The ‘General Table of Asian Languages’ in Balbi’s atlas includes the Rooinga and translations of words in the Rohingya language.

Ethnographic Atlas of the Globe

or Classification of Ancient and Modern Peoples According to Language

Adrian Balbi, 1826

Appendix VI

#69 Rooinga - by the Rooinga or Ruinga, who are the Mohammedans formerly established in the kingdom of Aracan. They still live in this kingdom and in the Burmese empire, of which it is part. This language is a mixture of Hindi and Ruk'henge-barma with Arabic words.

(translated from original French)

1872

From 1824-1937, Burma was a ‘province’ of British India. The first census conducted in the province of Burma occurred in 1872. While large numbers of people from India immigrated into Burma during British colonial times, the 1872 census and future censuses acknowledge the Muslim community in Arakan (Akyab District) as indigenous to Burma.

THE CENSUS OF BRITISH BURMA, 1872

Chapter VI: Population By Sex, p. 15-16

#75 Mahomedans, as noticed below, are indigenous only in Arakan, where two-thirds of the total number for the province reside.

#79 The Mussulman population of Akyab, however, is not, as elsewhere in the province, alien, as they have for the most part been settled in the province for many generations…

1891

Dr. Emil Forchhammer’s book: ARAKAN: An Account of his Archaeological Discoveries was published in 1891.

Royal Asiatic Society: GB 891 EF

Dr. Emil Forchhammer was a professor at Rangoon University. He was the first Superintendent of the Burma Archaeological Survey. He traveled to Arakan in 1885 and produced a detailed survey about history, language and religious sites in Arakan. His writings show the historical relationship between Buddhism, Hinduism and Islam and the people of these faiths in Arakan. The book, ARAKAN: An Account of his Archaeological Discoveries, was published in 1891. The book includes several photographs of mosques, including the Buddermokan Mosque (Plate XLII, No 88). It was constructed in 1756 and is located on the Kaladan River in Sittwe. The mosque was updated in 1849. The photo shows what the mosque looked like during Forchammer’s visit.

1891

Pages from Emil Forchhammer’s book, Arakan, published in 1891, including the Buddermokan Mosque (Plate XLII, No 88 - left).

ARAKAN

Emil Forchhammer, 1891

Chapter III: p. 60

There are a few modern temples in Akyab, which are interesting inasmuch as the architectural style is a mixture of Burmese turreted pagoda and Mahomedan four-cornered minaret structure surmounted by a hemispherical cupola. Plates XLII and XLIII show examples…both temples are visited by Mahomedans and Buddhists, and the Buddermokan has also its Hindu votaries.

The Buddermokan (Plate XLII, No 88) is said to be founded in A.D. 1756 by the Mussulmans in memory of Budder Auliah, who they regard as an eminent saint.

1911

REPORT ON THE CENSUS OF BURMA, 1911

Part I, Chapter IV: Religion, p. 98

92. Mahomedanism - … especially in the Akyab and Mergui Districts, are to be found indigenous Mahomedans, scarcely differentiated from the neighbouring Arakanese or Burmese in dress and speech and customs, the descendants of immigrants to the province many generations ago, yet who maintain their Mahomedan religion unaffected by the strength of their Buddhist surroundings.

1931

The category of ‘Indian’ was used widely in British censuses conducted in 1921 and 1931 to describe anyone who belonged to one of the ‘races’ of India, regardless of how long they had resided in Burma. These census reports also described those Muslims settled in Arakan (Akyab district) for generations as ‘indigenous’.

CENSUS OF INDIA, 1931

BURMA, Part 1 - Report

Vol XI, Part I, Chapter IV: Religion, p. 98

25. In parts of Akyab district, Indians [Muslims] are so numerous that they should perhaps be regarded as indigenous. This also applies to the Chinese in the Northern Shan States.

1936

British Library: MFM.M.C. 1198

The Government of Burma Act in 1935 separated Burma from India and provided the people of Burma with more self-government. Only two elections were held before Burma’s independence. The first election was held in November 1936. E.G. Maracan from North Arakan was elected to the newly formed House of Representatives. News clippings from the Rangoon Gazette announce the election results.

1941

When Burma was a province of India, migration was unrestricted between both India and Burma. This increased immigration of people and seasonal workers from India into Burma. The early 1900s saw a rise of anti-Indian and anti-British sentiment in Burma. In 1940, James Baxter was commissioned to write an inquiry on Indian immigration into Burma. In the report, long-settled Muslim communities in Arakan were described as indigenous to Burma and not foreigners.

REPORT ON INDIAN IMMIGRATION

by JAMES BAXTER

Dated Rangoon, 12th October, 1940

Page 4

7. There was an Arakanese Muslim community settled so long in Akyab District that it had for all intents and purposes to be regarded as an indigenous race.

1947

News clippings from the New Times of Burma announcing the results of the 1947 elections.

IOR/M/4/2605

In March 1947, political parties made nominations for candidates for the Constituent Assembly. In April 1947, elections were held. Sultan Ahmed and M.A. Gaffar from Maungdaw and Buthidaung in North Arakan were elected into the Constituent Assembly.

“The 1947 Constitution of Burma clearly states that people who resided in Burma on Independence Day, 1948, January 4th, were citizens. So to determine whether we are citizens or not, it is needed to start from 1947, not going back 100 or 200 years. That is the right way. We need to understand that we all belonged to Burma since the day of Independence.”

Aman Ullah, Rohingya elder

2023

1951

The front page of The Nation newspaper on December 4, 1951.

MFM.MC1195

Burma’s first election after Independence was held in 1951. Sultan Ahmed and M.A. Gaffar were re-elected. Sultan Ahmed’s wife, Daw Aye Nyunt (Zura Begum) was one of the first women elected into Burma’s Parliament. The front page of The Nation newspaper on December 4, 1951 announces the election results. On December 12, 1951 Burma’s first President, Sao Shwe Thaik, held a dinner party in Akyab. Sultan Ahmed and his wife both attended the party.

1954

“Located to the southwest of the Union is Rakhine State. There are two townships [there] called Maungdaw and Buthidaung. The nationals of the Union living in these two townships are Rohingya nationals and they are Muslims.”

U Nu

Burma’s First Prime Minister

1954

On September 25, 1954 Burma’s Prime Minister, U Nu, gave a radio broadcast. In the national broadcast he spoke about Arakan (Rakhine state today) and the Rohingya community. Here is an original transcript of his speech published by the government.

1956

Election results published In The Nation on May 6, 1956.

MFM.MC1195

In the 1956 elections, Sultan Ahmed, M.A. Gaffar and Abdul Bashor were elected as Members of Parliament. In a by-election in 1957 Rohingya voters were crucial in the election of Sultan Mahmud who became an MP representing Buthidaung. On June 18, 1958 he was appointed the Minister of Health.

1960

Articles from The Nation newspaper on December 27, 1959, January 16 and July 10, 1960, reporting on Shan & Kachin areas added to the Frontier Areas Administration (FAA) as well as the creation of the Mayu Frontier District in North Arakan. The background image is the cover of Khit Yay Magazine, July 18, 1961 with Mayu Special Edition.

British Library: MFM.MC1199B

1959-60 - In late 1959 areas in Shan and Kachin States along the Burma/China border were put under the control of the government department, the Frontier Areas Administration (FAA). At the same time, Arakanese Buddhists were close to establishing Arakan as an autonomous state. Rohingya opposed Arakan statehood primarily out of fear of Arakanese Buddhist dominance. Rohingya pressured the government to establish a special administrative zone in North Arakan under the control of the FAA. On July 10, 1960 The Nation newspaper reported the FAA had created the special Mayu Frontier District consisting of Maungdaw, Buthidaung and part of Rathedaung townships in North Arakan.

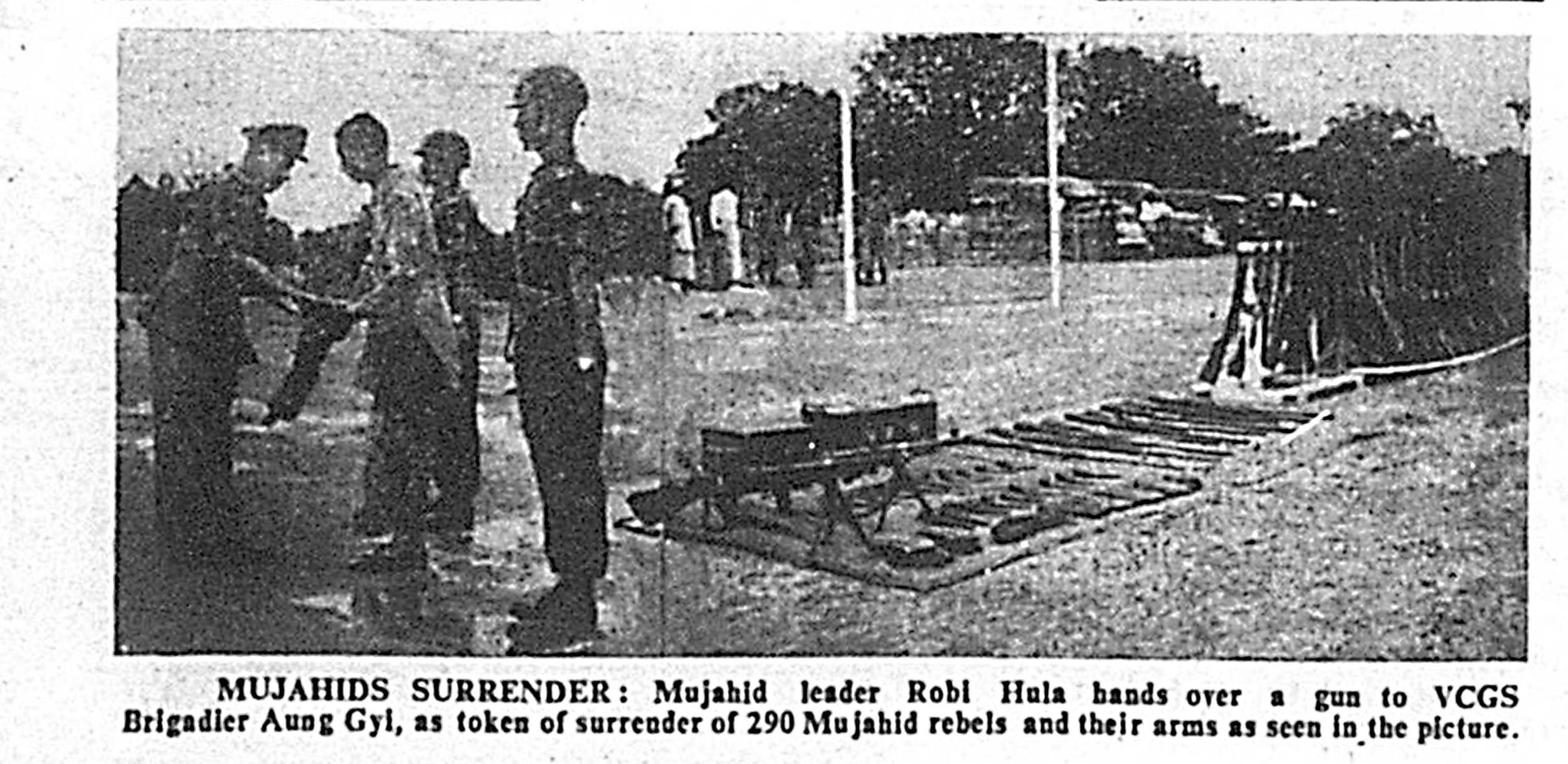

1961

Frontpage article in July 6, 1961 Guardian Newspaper (Burma) about the Mayu Frontier District, the surrender of Mujahid rebels and acknowledgement of the ‘Rohinja’ community by Brig General Aung Gyi in his speech.

1961 - During World War II, the Muslim and Buddhist communities in Arakan fought for different sides. The Muslims serving for the British. The Buddhists serving for the Japanese. This created a significant division between the two communities. Muslims fled to North Arakan. Buddhists fled to south Arakan. In the late 1940s and 1950s, ethnic insurgencies spread throughout Burma. In Arakan, Muslim insurgents (Mujahids) emerged as a result of the divide created during WWII. They fought against the government and also wreaked havoc on local Muslim communities. By the early 1960s, the Mujahid had lost broad support from many Rohingya. After the administration for the Mayu Frontier District started in May 1961, hundreds of Mujahid insurgents surrendered their arms to the government. At the most significant surrender ceremony in July 1961, Brigadier General Aung Gyi, acknowledged the Rohingya as one of the ethnic minorities belonging to the Union of Burma and said the government was committed to economic development, equality and inclusion for the Rohingya in Arakan.

On March 1, 1962 the government canceled the proposal for the creation of an autonomous Arakan state. On March 2, 1962 General Ne Win seized power in a military coup. In 1964, two years after the coup, the Mayu Frontier District was dissolved.

1961

The Nation reporting the creation of the Rohingya language program on April 21 & August 20, 1961.

On Friday April 21, 1961 Burma Broadcasting Service announced ‘more broadcasts in national languages’. Programmes for both the ‘Rohinja’ and the Arakanese Buddhist (Rakhine) communities were added. The actual broadcasts began on August 22, 1961.

“I was born in Arakan, went to school and then studied in India for eight years. I returned home to Burma and became a teacher. I wrote three books. I wrote for one year. I didn’t stop writing. The scars from writing are still on my fingers.

“Once a week I would recite the Koran on the radio and then tell the news in the Rohingya language. The Rohingya language program on Burma Broadcasting started in 1961 but was then canceled in 1965. We were very sad when our program was canceled. Then, we all were the same. We all had equal rights and enjoyed life. Now, nothing is left.”

Irshad Hussein, Rohingya elder

2018

30th Anniversary of Burmese Broadcasting Service

Language Programs, ten minutes each in Mon, Pau, Lahu and Rohinja were broadcasted starting from May 15, 1961.

Irshad sits in his hut in a refugee camp in Bangladesh. He was one of the original Rohingya radio broadcasters in the early 1960s. Along with 700,000 other Rohingya, he was forced out of Myanmar during a campaign of genocidal violence in 2017. Irshad passed away in 2021. He was 108 years old.

1964

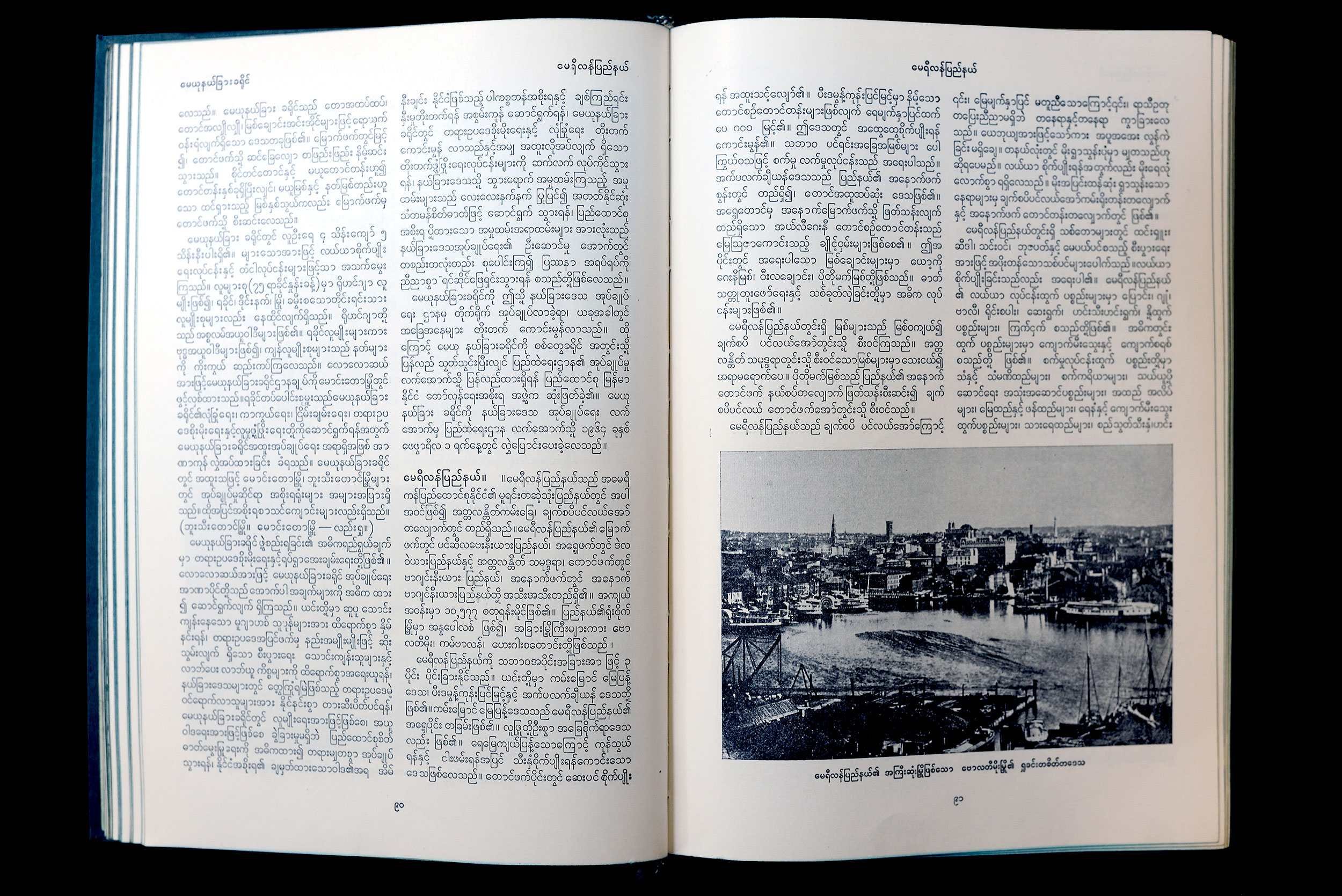

Myanmar Encyclopedia, 1964

Government Printing House, Rangoon Vol 9.

There are over 400,000 to 500,000 population in the autonomous district of Mayu. Most of them make their livings by doing agriculture and fishing. The majority, making up 75% of the population are the Rohingya ethnic people and the other majority native people such as Rakhine, Dinet, Mro and Khami are also living in the region. The Rohingya are the believers in Islam.

(p. 90)

“I am tired of giving and providing historical references and all this effort to be indigenous. We don’t need to give references. We are tired of giving it.

“Arakan has been home to us since it was an independent kingdom. Muslims were administrators. Literary contributions were done by Muslims. Agricultural and economic development were made by Muslims. What have we not done! You can’t deny we didn’t have a contribution. Arakan is our contribution. Our contributions would make Arakan great within Burma.”

Nurul Islam, Rohingya elder, (2023)