6

Evidence of Existence

Stories of family, belonging and what remains

“They want to say we are not from this country. They want to make us Bengali. They chase us from the country. They have done a number of clearance operations before. If we can, one day, show them these documents, they cannot say we are Bengali. They cannot make us Bengali. They must give us ethnic nationality.”

Nur Alam, Rohingya elder,

2018

As a British colony for nearly 124 years, the administration of Burma operated through an extensive bureaucratic system. Records, documentation and other forms of paperwork served as formal (and legal) evidence related to legal status, employment, land ownership, taxation, personal and family registration, pension benefits, travel, business and trade as well as political participation. At one time, North Arakan was one of the most heavily administered areas in all of Burma. This bureaucracy continued after Burma became independent.

Through decades of oppressive policies and within a broken and discriminatory legal system put in place by successive military regimes, this documentation held little value. Even while subjected to harsh persecution, violence and displacement, Rohingya hid and preserved documentation of their family’s heritage and historical connection to Arakan. This documentation was then carefully passed down from one generation to the next, often times stored away secretly out of sight. The ‘clearance operations’ and mass expulsion of hundreds of thousands of Rohingya into Bangladesh in 2017 was unprecedented. In the chaos, violence and total destruction of homes and entire villages, Rohingya miraculously carried with them the last remaining shreds of their family’s documentary heritage. In some situations, this included portfolios and bundles of fragile papers dating back to the 1800s.

In this chapter, these ‘portfolios’ are followed by testimonies of individuals talking about the significance of the past and the importance of these materials today. Individually, each portfolio of documents tells the story of one person, or one family. Collectively, they share the story of the Rohingya’s existence as a community belonging and contributing to Burma.

Land documents, land tax payments and legal land settlements from Attar’s family date back to the early 1900’s. The documents also show Rohingya land ownership in the 1800s.

“We are the descendants of a big family from Boli Bazar. These land documents are gathered for Rohingya to show as their evidence. That is why my father and others kept them. Whatever the Burmese government says, we have these documents. If I have these documents, I can tell my family history and I can say that the descendants of this family will never disappear.”

Attar H, 35

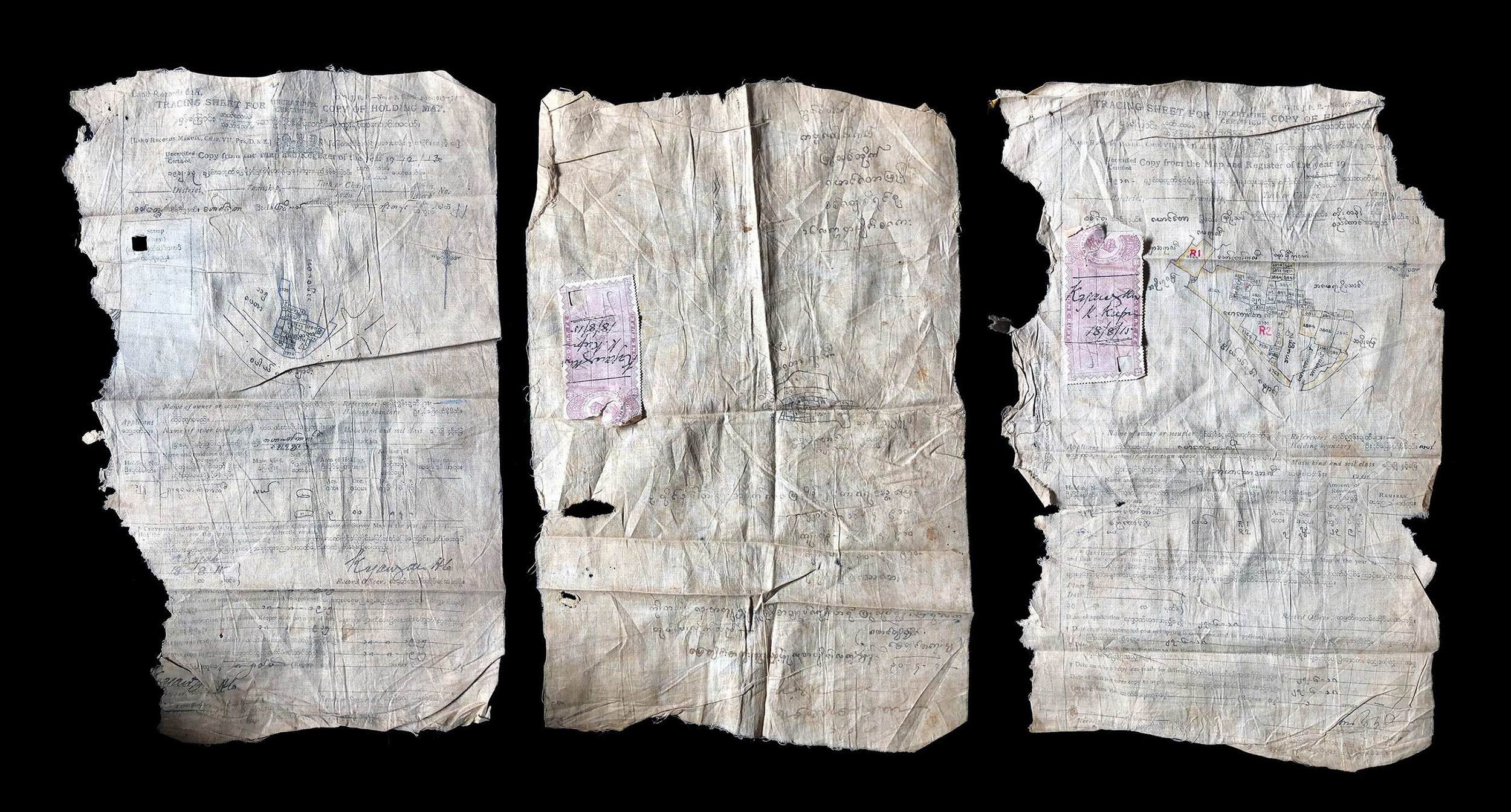

Family documents of one Rohingya family from Maungdaw. The document on the right is an ownership document for a ‘grand patta’ of land. The document was written on April 13, 1881.

“My father told me that long ago we were all the same. We all lived together with other people. My parents said their lives in the past were peaceful times. After I was born, when I was growing up, they said they are getting worried. They told me, These people will drive us out someday. I believe all of these documents are proof that we are originally from Arakan. Look back at all of this and you will see who we are and how long we have been here.”

Nurul B, 60

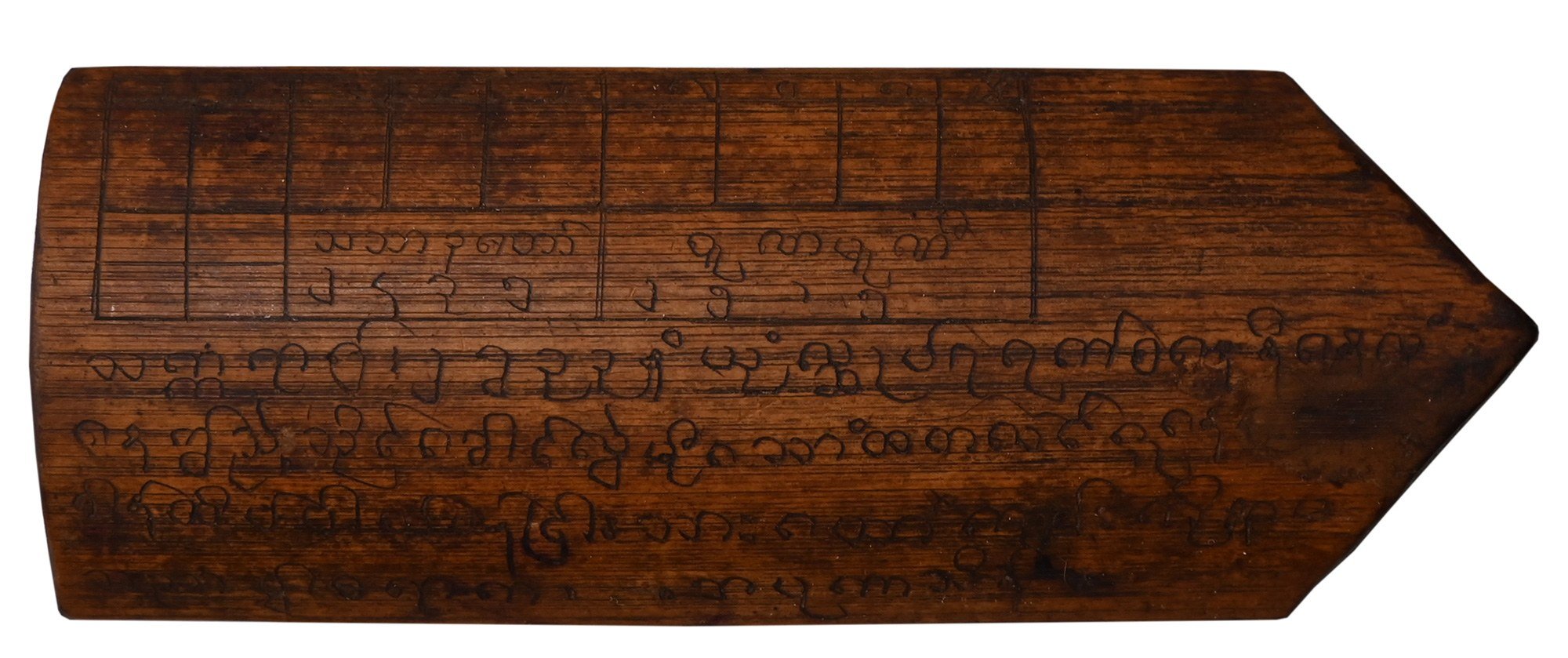

Inscribed into a piece of bamboo, this is a manuscript of land ownership from a Rohingya family from Maungdaw. The document dates to 1892.

Land documents with property maps issued on cloth and fabric to the ancestors of Nur S. from Maungdaw. The documents date 1910-1915.

Salai Ahmed (center) was appointed a village headman in 1949. He passed away in the late 1980s. Included here are: original National Registration Cards of Salai Ahmed, his brother and son and their wives, a Family list issued in 1959 and Appointment of Headman issued in 1949. Also two voter registration cards issued in 1978 and 1981 by the electoral commission.

“My grandfather was a village headman for almost 40 years. He was an Arabic school teacher. He was respected by many people and was a member of the local council. My family owned a lot of land and we lived in Maungdaw for several generations.”

Rohim U,

Grandson of Salai Ahmed.

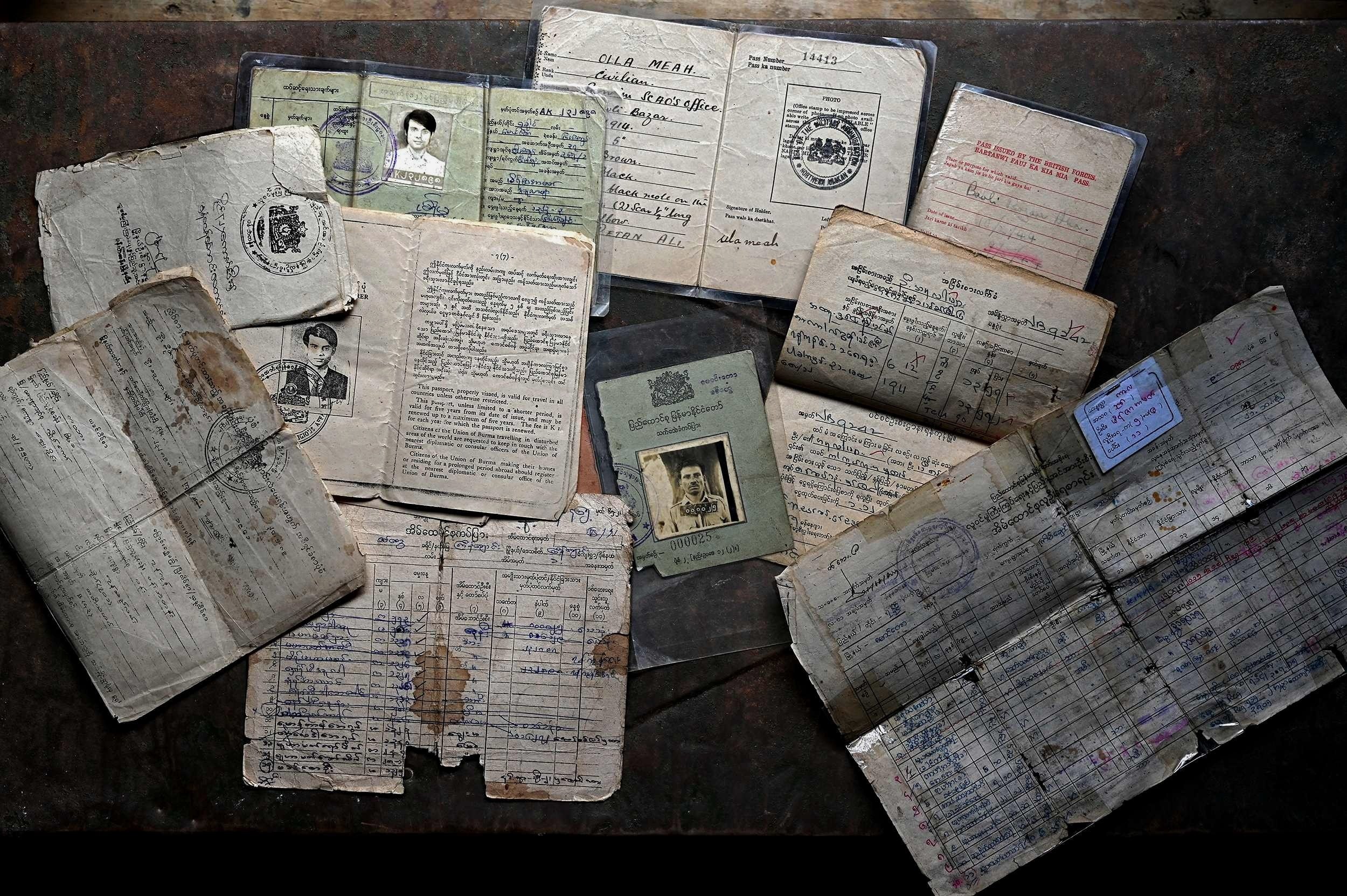

Olla Meah (center) served for the British in “V” Force during WWII. He was a Rohingya community leader in the 1940s during Burma’s Independence. His son (upper left) became a teacher.

In the mid-1950s, the first National Registration Cards issued in Burma were issued in a pilot program starting in North Arakan. His ID card number is 00025. It is believed Olla Meah was issued one of the earliest NRC cards.

“My father worked for the government since 1944. He was a volunteer and was responsible for distributing rations during the British Administration. After independence he joined the Customs Department. He retired in 1966. The National Registration Card (NRC) provided to my father is numbered, 000025. It is the 25th NRC card issued in the whole of Burma. If my father was not a citizen, he could not have this card and a government job. My grandfather, great grandfather and great-great grandfather were born in this country and we are descendants of them.”

Mirza A, 61

Son of Olla Meah

Titled, Record Of The Descendants From Haru and Daw Pay Thi this handwritten book provides the history of one family from Buthidaung. While the birthdate of the patriarch, Haru, is estimated to be 1829, the family tree in this book begins in 1868.

“My grandfather was a judge and my father was a teacher. One of the oldest mosques, the Mee Kyaung Zay mosque built in 1854 is in my village. Before my uncle died, he and my father sat down and recorded our family history. They went back as far as they could go. The family history in this book goes back to 1868.”

Nojibul

Grandson of Abul Hushin

Ula Mea (upper right) became a policeman in 1952. He was highly decorated for his service. In the 1950s, armed insurgencies were occurring throughout Burma, including in Arakan, which were referred to by the Burmese press as Mujahids. In 1956/57, Ula Mea was responsible for the arrest of a leading Mujahid commander in Arakan.

Included are Ula Mea’s policeman ID, Good Service Certificates, Police ‘Do’s & Don’t’ book. After retiring he received a government pension. His pension book is also included.

“My grandfather was a policeman and my father was a policeman…a sergeant. He retired in 1995. We were so proud of him. That is why my brothers also served in the police and my brother-in-law in the military. We were proud of them for their service for the country.”

Gura M

Grandson of Ula Mea

Ula Mea’s son, Din Islam (sitting fifth in front row) became a 2nd generation police officer and a head trainer in a police training academy.

In 1924, Lawshkara Ali from Maungdaw was appointed the position of Se-Ein Gaung, or a rural policeman.

Taza Mulluk was born in 1941. In 1961, he became a government employee at Burma Telecommunication Service. He then became a postman. In 1965, he was forced to change his name to a Burmese name, U Ba Tun.

He retired as a postman and received a government pension. Included are ID cards from his employment at Burma Telecom and Burma Postal Service, his pension book and NRC card, a list of all the postmen in Arakan at that time and a photo of Taza Mulluk retired with two other colleagues from the postal service.

“My grandfather received his uniform from the government. I saw his uniform when it was put out to dry under the sun. I used to think to myself whether he was in the military or the police. My parents told me he was a postman. He got sick and I had to accompany him wherever he went. I remember seeing the Rakhine respect my father by putting their heads down when we went out on the road.”

Mohammed A (23)

Grandson of Tullah Muzak

Mohammed Alom’s university graduation photograph in 1988. He became a doctor in 1995.

“This is my father. After three years of studies in university he graduated from Yangon University. This is his graduation photograph. He then became a doctor. All of these photographs are memories of my family, and I’ve kept them so that if anything happens in our country, we can prove who we are.”

Ibrahim (31)

Son of Mohammed Alom

Irshad Hussein was born in Maungdaw. He lived to the age of 106. He died in the refugee camps in Bangladesh. Displayed are some of his writings as well as the NRC card of his son.

“My father was writing all the time. He wrote poems and stories. His small poetry book has Urdu on the left and Farsi on the right. He recited the Quran on the Rohingya language radio program.

“My father said that when people came to talk with him about Rohingya history, he would tell them we have been living in Arakan for 500 years, at a time when there was no Myanmar government.”

Rashid H (61)

Son of Irshad Hussein

“Nearly all the documents of my family were destroyed in the fire. The documents go back over 80 years.”

Mohammed Y (79)

On March 5, 2023, a fire destroyed a section of the Balukhali Rohingya refugee camp in southern Bangladesh. Over 2,000 shelters were destroyed. All of the family documents Mohammed Yunus (79) carried with him when he fled Burma in 2017 were destroyed.

Along with shelters, the fires destroy the last remaining evidence many Rohingya families possess of their family history and connection to Burma.