7

Resistance

Movements for liberation, preservation and the restoration of rights

“The political culture in Burma, every community had their movement, their armed movement. But there were two movements simultaneously under one: one was from the jungle, one was in the parliament. Our leaders fought through parliament. Similarly we also needed a movement in self-defense. If Rohingya could not develop their armed struggle, they would be finished.

“But the basic difference, the fundamental difference, is Rohingya existence is always at stake.”

Nurul Islam, Rohingya elder,

2023

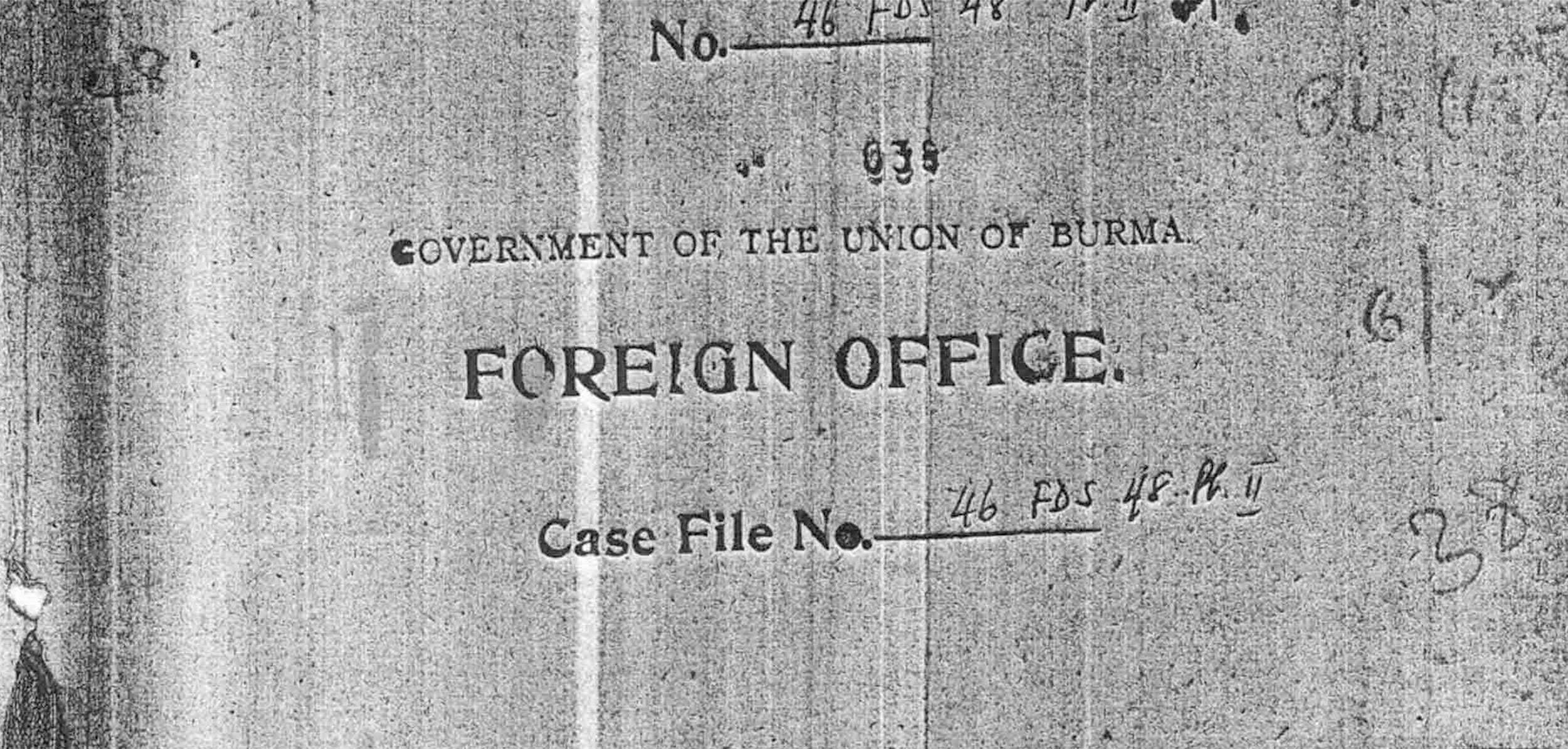

Since independence in 1948, Burma has been the site of one of the world’s longest running civil wars. Many ethnic minority communities had been excluded in negotiating the structure of the new state leading up to independence. As a result of this, and a flawed Constitution that didn't fully address ethnic minority rights, communities began to oppose the policies of the central government, in particular demanding more autonomy. During the late 1940s and early 1950s, communists and ethnic national groups throughout the country armed themselves and waged insurgencies against the government. By the 1960s and 1970s, the socialist government and military (Tatmadaw) were aggressively expanding efforts to control and oppress ethnic minorities. The Karen, Karenni, Mon, Pa’O, Rakhine (Arakanese Buddhist), Kachin, Chin, Shan and other communities fought against the Tatmadaw. Correspondence, newspaper reports, op-ed pieces, along with original photographs and a rare collection of printed magazines from various Rohingya liberation groups show how the Rohingya resisted through public voice, political channels, and, like other ethnic groups in the country, armed struggle. They sought to defend and liberate their community while standing in solidarity with others against an increasingly oppressive military regime.

1948 - In the months and years following Burma’s Independence in January 1948, ethnic insurgencies were raging in many areas across Burma, including Arakan. Arakanese Buddhist nationalists and Muslim separatists (called ‘Mujahid’ at that time) were fighting and rebelling against government forces. Local communities were terrorized in the lawlessness. Newspapers at the time consistently published front-page stories about the lawlessness in Arakan. Established in 1936, the Jamait ul-Ulema was the political voice for Muslims in Arakan, especially those in North Arakan. Before a proposed visit to North Arakan by Burma’s Prime Minister, U Nu in October 1948, the Jamiat ul-Ulema wrote a welcome address expressing their loyalty to the Union of Burma and their demand to be seen as a community belonging to Burma.

1949 - In North Arakan, Muslim separatists were fighting against government forces and terrorizing local Muslim communities. Government forces and Arakanese Buddhists were committing atrocities against the local Muslim community as well. By May 1949, up to 7,000 Muslim refugees from North Arakan had fled across the border to East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). The Central Arakanese Muslim Refugee Committee had sent several letters to the central government protesting the violence in North Arakan. On December 22, 1949, refugee leaders of The Central Arakanese Muslim Refugee Committee gathered in the East Pakistan town of Teknaf on the border with Burma. They drafted several resolutions which detailed the atrocities committed against the Muslim community in North Arakan. Still expressing loyalty to the Union of Burma, the Muslim community claimed it would prepare itself for self-defense and the restoration of peace and asked not to be viewed as an insurgent movement but as a community defending itself against the oppression of others.

1954 - In 1953/54, Burma conducted its first post-independence census. During the census attempts were made to categorize Rohingya as ‘Indian or Pakistani’. On December 24, 1954, more than 5000 Rohingya held a mass meeting in Maungdaw to protest this and demand Rohingya be categorized with other races indigenous to Burma. Rohingya MPs Sultan Ahmed and Abul Bashor spoke at the meeting. The meeting was reported in the New Times of Burma on January 8, 1955.

Headlines from articles in The Nation and The New Times of Burma in 1958 and 1959.

1950s - Ethnic communities like the Karen, Karenni, Mon, Pa-O and Arakanese (Rakhine Buddhist) had taken over control of large sections of the country through armed insurgencies. In an effort to stabilize the country, U Nu initiated peace efforts. The “arms for democracy” policy led to the mass surrender of rebels from many of these groups. In the 1960s these armed conflicts escalated and more communities, like the Shan, Kachin and Chin formed their own ethnic insurgencies.

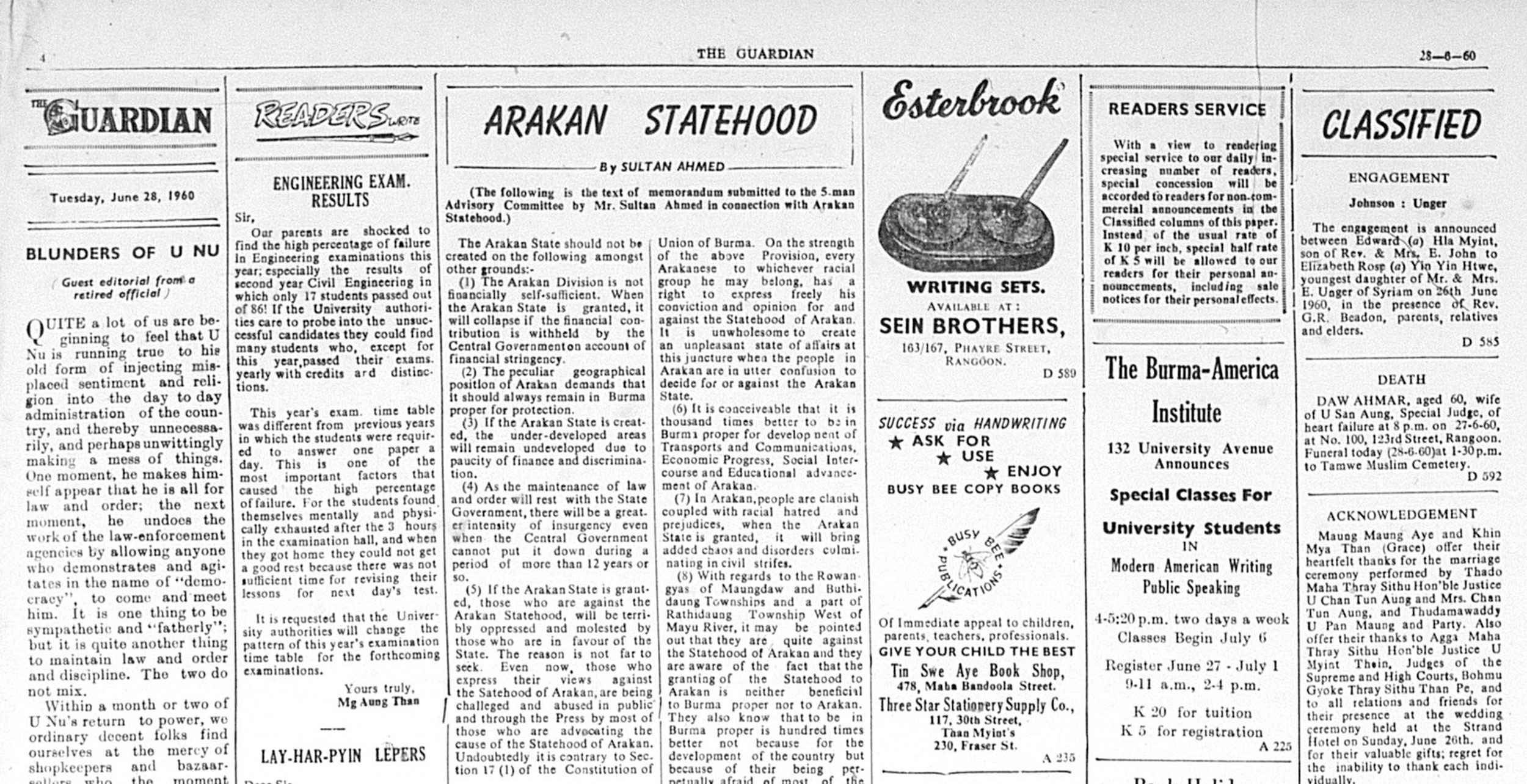

1958 - In early 1958, the Arakanese Buddhist community and its primary political party moved to establish an Arakan State. The proposed state would be administered by the Arakanese Buddhist community. Rebels from the community laid down their arms hoping this gesture would help forward efforts for statehood. Arakanese statehood was widely discussed for the next three years and covered prominently by newspapers like The Nation, The Guardian and The New Times of Burma. In 1960, Prime Minister, U Nu promised statehood for Arakan, yet many, including the Rohingya, were strongly opposed to it.

1960 - The Muslim community in Arakan were opposed to the creation of an Arakan State. The Rohingya wanted the administration for Arakan to remain with the central government. Rohingya leaders felt a new state would establish an Arakanese Buddhist-controlled state and place the Arakanese Buddhist community in the dominant position economically and politically. Former Rohingya MP and Ex-Parliamentary Secretary, Sultan Ahmed provided eight reasons for the opposition to the creation of an Arakan State. This ‘memorandum’ was submitted to an Advisory Committee exploring Arakan statehood. It was published in The Guardian newspaper on June, 28, 1960.

1960 - In late October 1960, representatives from the Muslim community in Arakan continued to oppose statehood. They did so on the grounds that, ‘22 points needed to be incorporated in the Constitution of the proposed Arakan State’. These were meant to provide ‘safeguards for the protection and promotion of the Muslim minorities’ religious, cultural, economic, political, administrative, educational and other rights’.

A July 9, 1961 article in The Guardian newspaper show how Mujahid had lost support in North Arakan. After the creation of Mayu Frontier District, Rohingya continued to oppose an Arakan State as reported by The Nation on November 28, 1961. The background image is the cover of Mayu Special Edition of Khit Yay Magazine published on July 18, 1961.

1961 - By the early 1960s, the Mujahid movement had lost momentum and support from many Rohingya. The Mayu Frontier District had been created where the townships in North Arakan remained under the control of the central government. Administration of the Mayu Frontier District in North Arakan began in May 1961. Hundreds of Mujahid insurgents surrendered their arms to the government. President U Nu had already promised the Arakanese Buddhist community statehood, but Rohingya and others continued to oppose the creation of an Arakan State. The Rohingya preferred to remain under the administration of the central government rather than in a state dominated by the Arakanese Buddhist community.

Articles printed in The Nation newspaper on March 1, 2 and 3 of 1962. They report the government cancellation of the creation of an Arakan state and General Ne Win’s seize of power in a military coup.

1962 - On March 1, 1962, the government canceled the proposal for the creation of an Arakan state. On March 2, 1962, General Ne Win seized power in a military coup. In 1964, two years after the coup, the Mayu Frontier District was dissolved. Twelve years later, with the Constitution of 1974, Rakhine State was created.

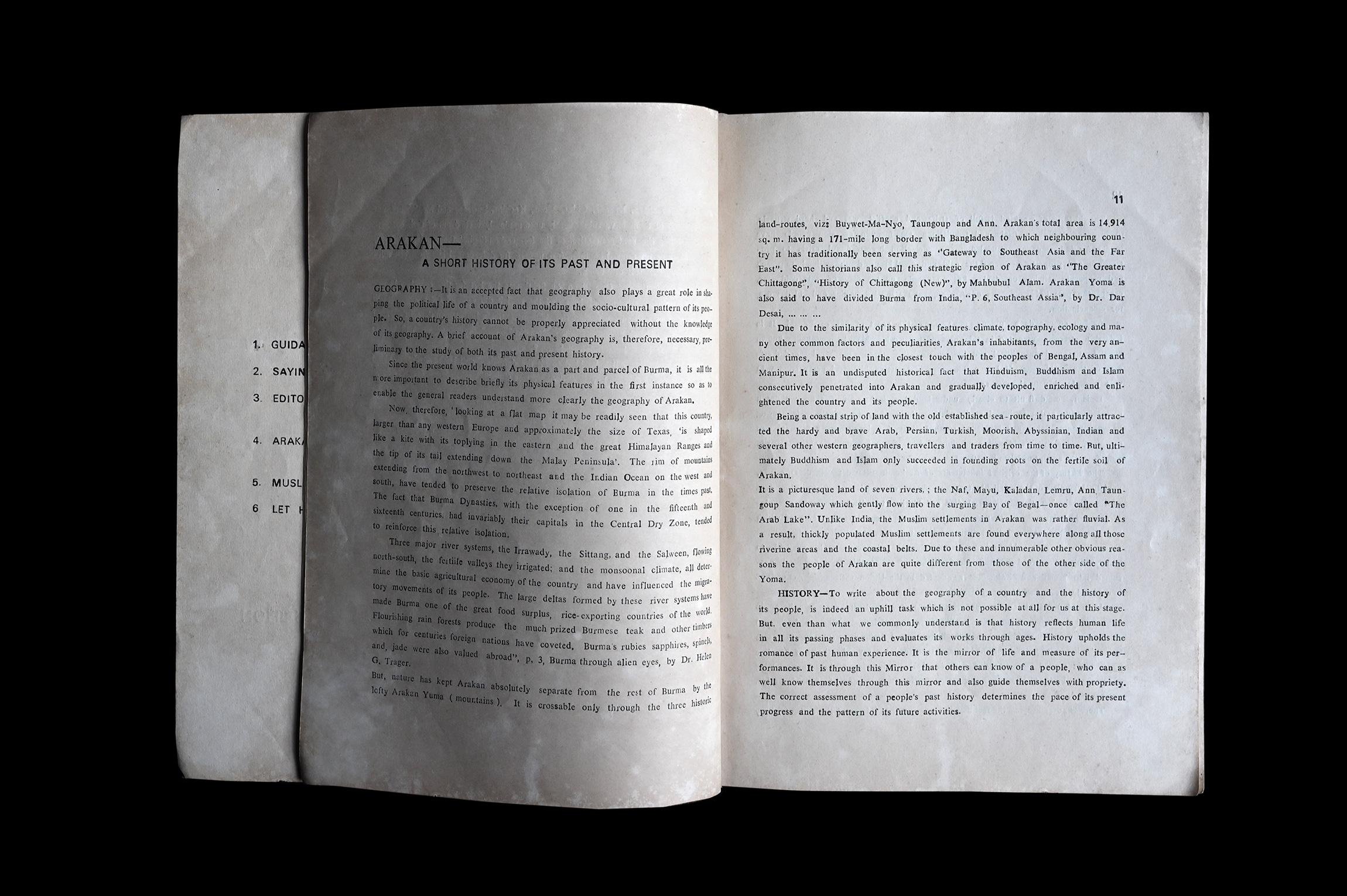

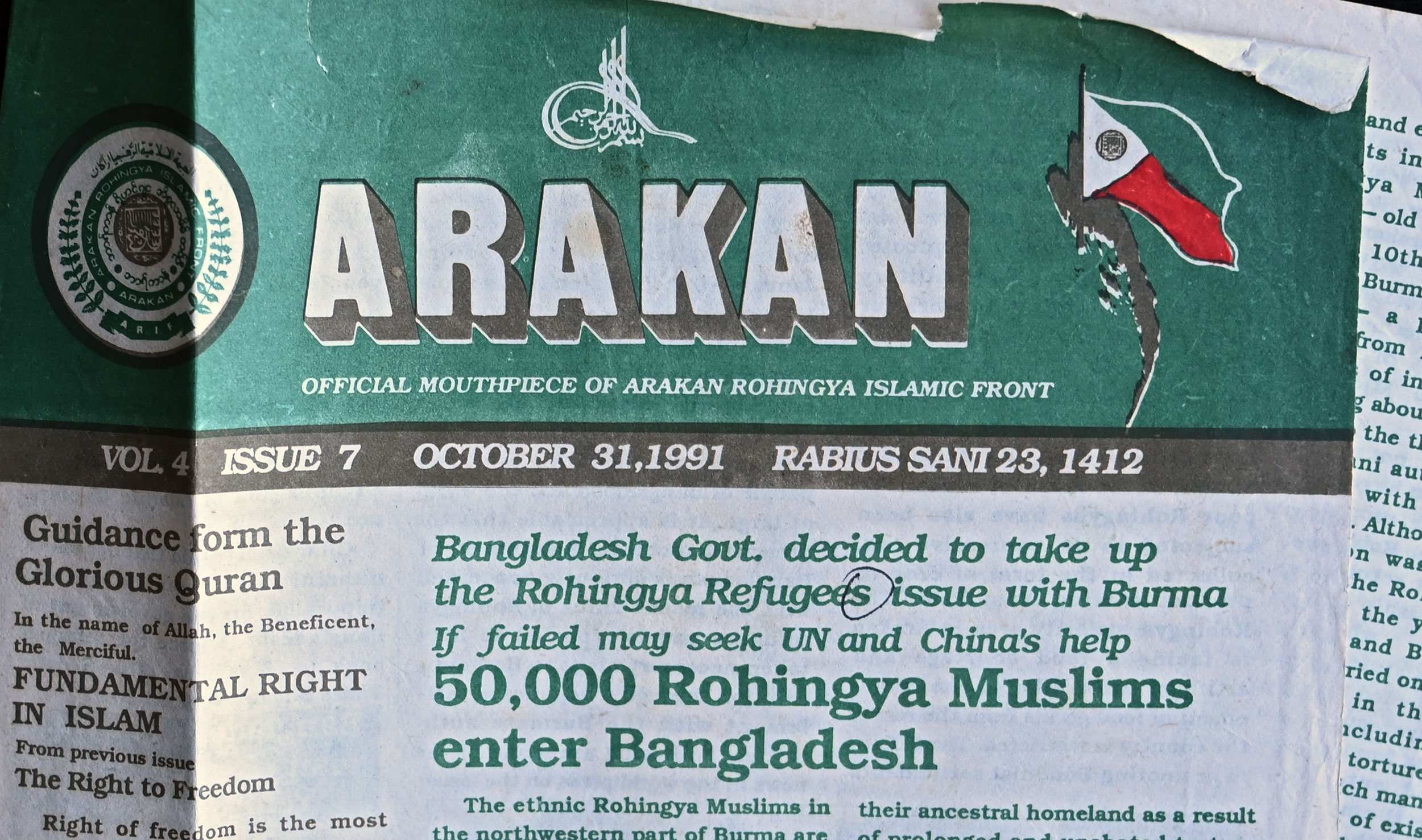

Rohingya liberation groups from the 1970s through the early 2000s published their own magazines and journals. The publications served as a voice for Rohingya to the international community. Magazines included historical pieces, analysis of current events in Burma and in depth updates on the persecution of the Rohingya community throughout these decades.

“We the Rohingyas are nothing else but true Burmese Nationals by birth, like other minority nationals most of whom settled in Burma much later than we the two sister communities of Arakan…Branding us as aliens, traitors, saboteures, autonomists and even separatists will not budge us an inch from our unswarving struggle for equal rights and freedoms…

“The power of the government lies with the people. Public sentiment is everything. With public sentiment nothing can fail; without it nothing can succeed…Aggression, repression, extermination, vandalism, barbarism, sham-patriotism and self-imposed pseudo-socialism have now become outfashioned, obnoxious and detestable. We are in Apollo age and the world now wants true democracy irrespective of colour and creed.”

“Where there had been aggression and oppression there was resistance. We shall also be ever ready to pay any price for our safety from the tyranny at the hands of the government…

“We have been involved in a real revolution—a revolution for immediate and full restoration of all our usurped Democratic Rights.

Excerpts from RFP publication, February 20, 1978

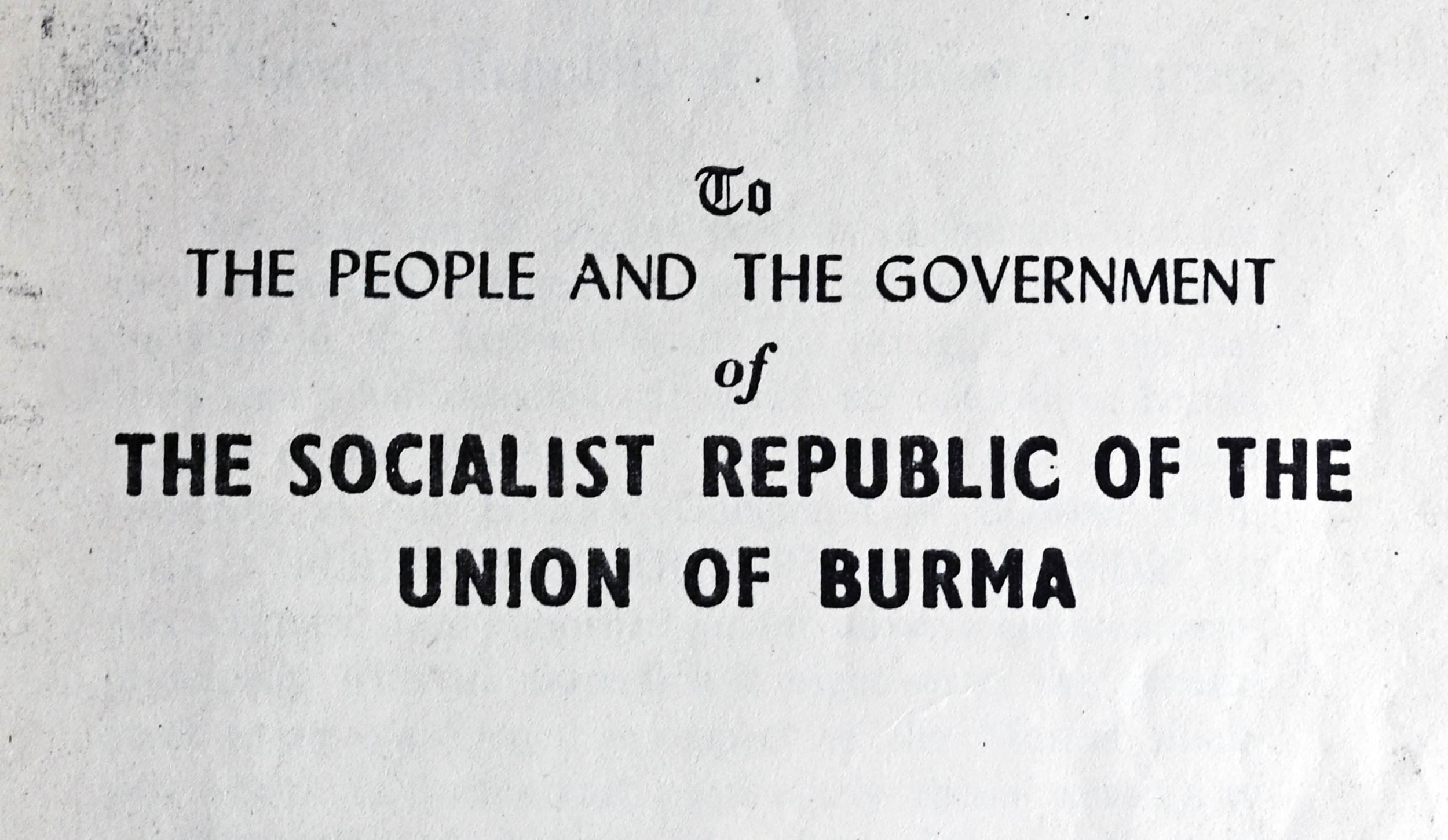

1978 - In 1973, a group of Rohingya insurgents created the Rohingya Patriotic Front. Ne Win’s policies were highly racialized and xenophobic against Muslim communities, especially the Rohingya in Arakan. Five years later, on February 6, 1978 immigration officials swept into Akyab launching the Naga Min Operation or Operation Dragon King. In Arakan, the operation was launched as an ‘immigration operation’ attempting to cut down on illegal ‘Bengali’ immigrants. Instead it targeted Rohingya with violence, arrests and killings. Tens of thousands of Rohingya fled into neighboring Bangladesh. On February 20, 1978 the Rohingya Patriotic Front printed this 20-page publication. It detailed the injustices of the Ne Win government, the atrocities being committed against Rohingya and described the operations as ‘Genocide and Apartheid’. It also included calls for an immediate stop of the operation along with five other demands.

Headlines from various newspapers such as The Bangladesh Times & Bangladesh Observer report the atrocities against Rohingya during the Naga Min Operation.

1978 - Over the course of three months, more than 200,000 Rohingya fled to Bangladesh. Most of the Rohingya who fled Operation Naga Min in 1978 were permitted to return to Burma, but Burmese authorities labeled them as Bengali ‘foreigners’.

“We the sentinal of the RPF, composed of thousands of die-hards from amongst the oppressed, repressed, snubbed and evicted Rohingyas, will leave no stone unturned, in achieving our complete emancipation…”

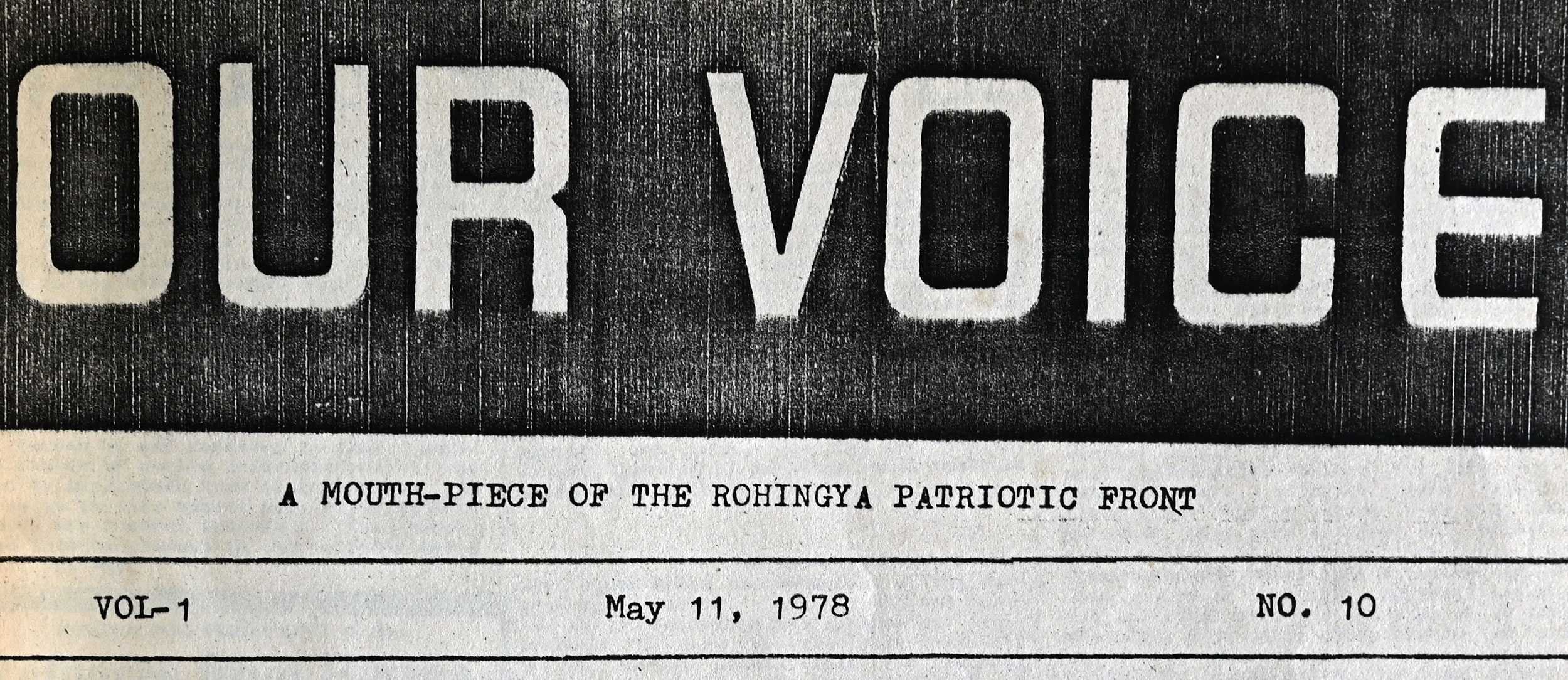

1978 - An early publication released by the Rohingya Patriotic Front was titled Our Voice. This issue from May 1978, condemned the Burmese government for the terror, violence and displacement inflicted on the Rohingya during Operation Naga Min in early 1978. It also reinforced the Rohingya demand for justice.

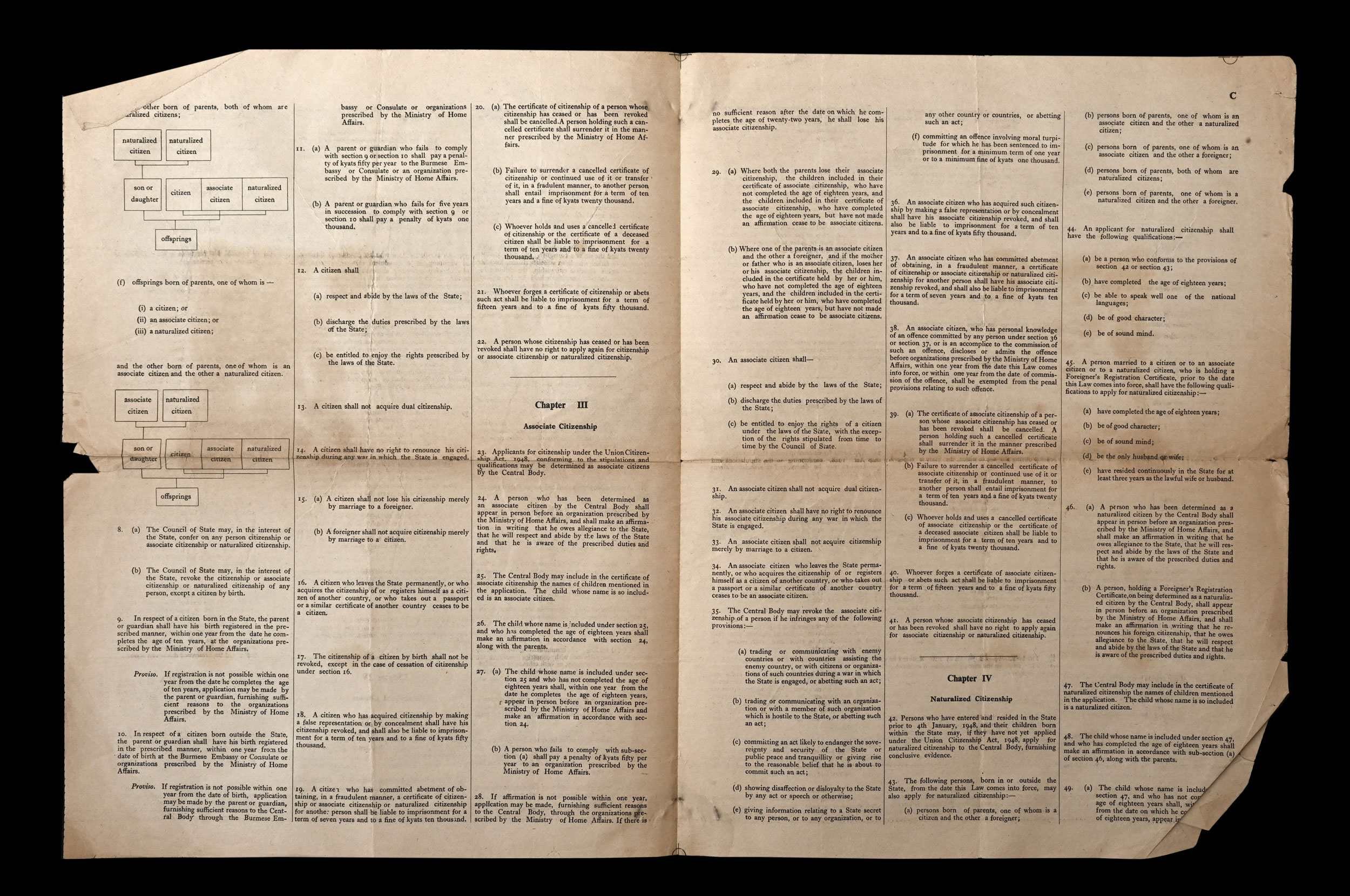

“CITIZENSHIP - The categorisation under this serial is but an artful maze intended only to bewilder the Rohingyas in particular…Burma is also an ethnological museum of scores of races who converged on its soil from far and wide. The Rohingyas have also the right being considered as one of them by virtue of their hoary convergence which no one can refute. It is their historic right.”

1982 - At the beginning of 1981, the Rohingya Patriotic Front (RPF) launched the magazine, Rohingya-R-Daak or The Call of the Rohingya. On July 4, 1980, an official communique was published in the Government Daily Journal Guardian introducing a draft of a new citizenship law. This issue of Rohingya-R-Daak, published in January 1982 (Vol. 2/Book 1) is almost entirely dedicated to challenging the legitimacy of the proposed new laws.

A special supplement published in the October 16, 1982 issue of the Working People’s Daily newspaper explains the details of the new 1982 Citizenship Law.

1982 - Ne Win’s government passed the controversial 1982 Citizenship Law. The law introduced three different categories of citizenship. Citizenship was now dependent on ethnic identity and recognition within Burma’s ‘national races’. These ‘national races’ were not defined at the time. The law stated that those who had citizenship would not lose it, including those from the Rohingya community.

In the 1970s, officials started confiscating Rohingya National Registration Cards which had served as their proof of citizenship. No longer recognized as one of Burma’s ‘national races’, unable to show evidence of previous citizenship and subjected to increasing levels of discrimination and racism from local immigration officials, most Rohingya were deprived of Burmese citizenship.

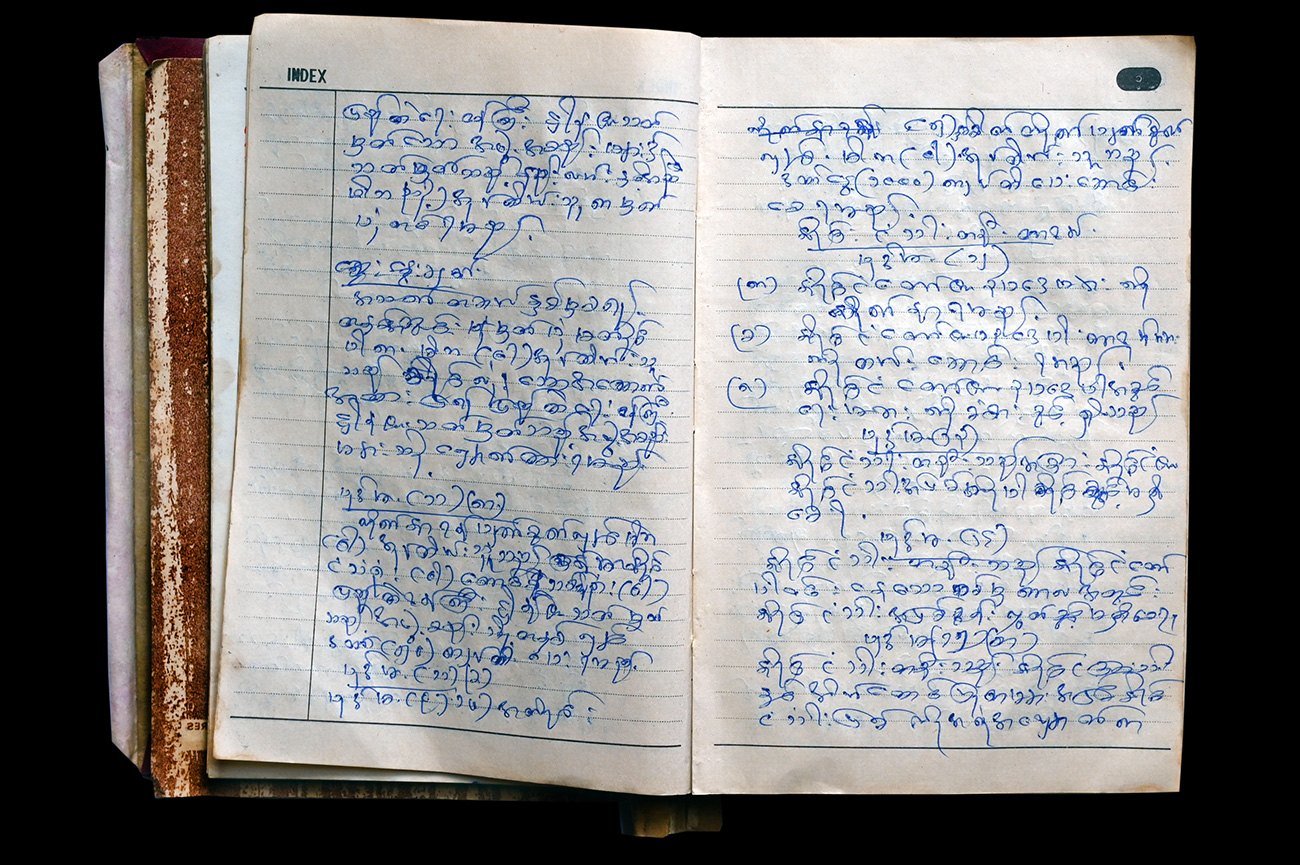

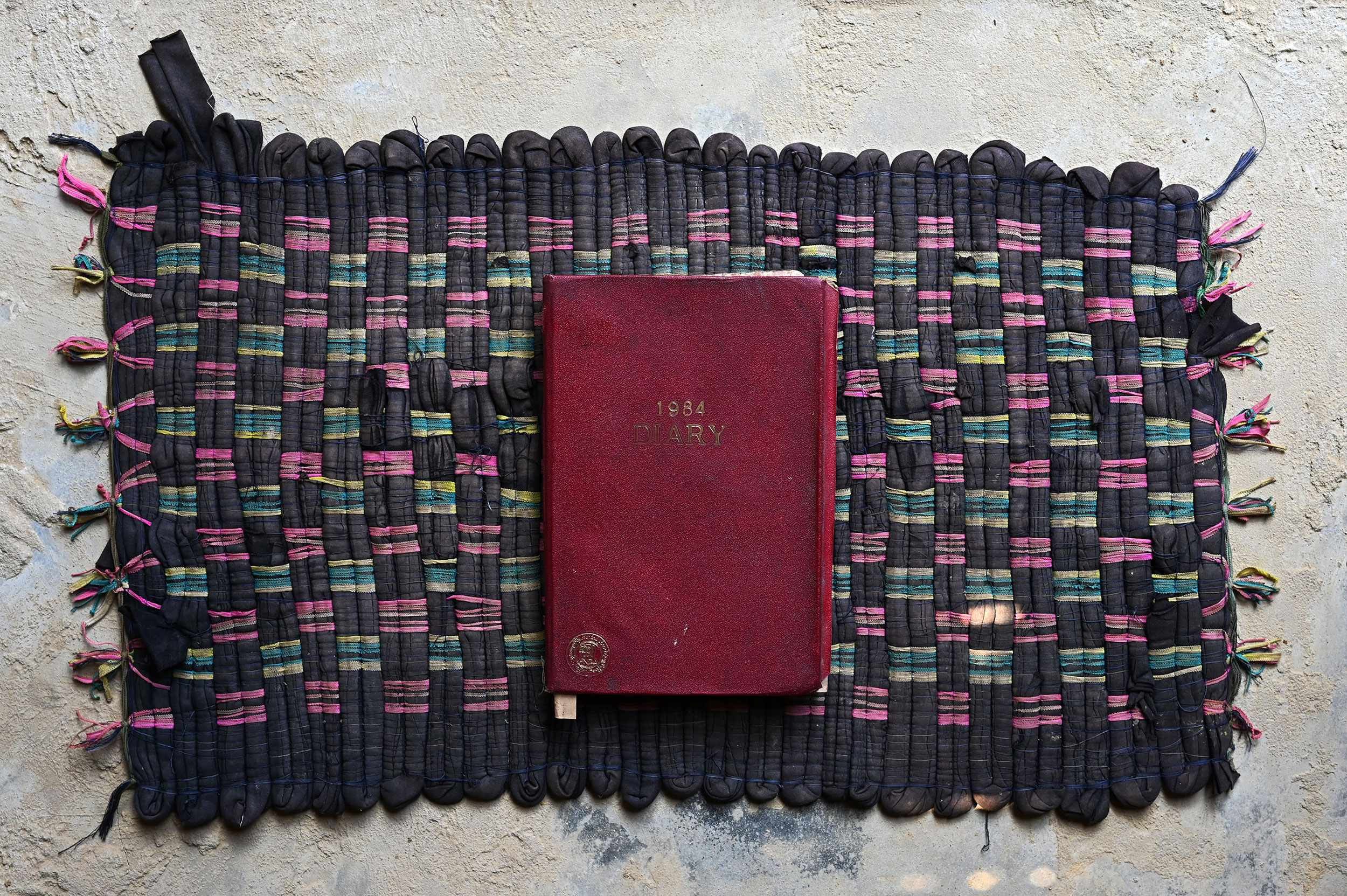

“They called us for a meeting to explain the new citizenship law. When the meeting started, the chairman was explaining the law. We were listening and taking note of it. I was writing as much as I could in my diary. Finally, when we learned they were using the citizenship law to discriminate against us, we felt like we were not part of the world anymore.”

Abul Kalam, 69

1984 - It took several years for the government to implement the 1982 Citizenship Law. In 1984, Abul Kalam attended a meeting where government officials informed village leaders about the 1982 Citizenship Law. He was responsible for communicating the details of the meeting back to others in the surrounding villages near his home. Page after page of Abul’s diary is filled with his notes from that meeting.

“On many a occasion people have fought for independence, struggled for emancipation, braced awful crises to protect life and property, embraced the cold and cruel kiss of death smilingly to preach and propagate religion or ideals. But no people on the clay of this cold star, except the potential Rohingyas of Arakan, have struggled harder and bled more, for emancipation….

“The Rohingyas, along with other Muslims of the country are now left absolutely at the mercy of Rangoon, and the Union Citizenship Act of 1982 was the last straw.”

1984 - In the early 1980s, several Rohingya split from the RPF and formed the Rohingya Solidarity Organization (RSO). The RSO launched the magazine INSAF, or Justice. This 11-page essay printed in INSAF on April 1, 1984 (Issue 1), confronts the realities of the 1982 Citizenship Law as well as Arakan/Rohingya history and the brutality of the oppressive Burmese regime.

1986 - Fighters from the Rohingya Solidarity Organization (R.S.O.) during guerrilla warfare exercises along the Burma/Bangladesh border.

“At the time of this photo, we were young and we felt encouraged. Our vision was to secure our own freedom. We must stand on our own feet. We must try. We had to inspire the young people and we had confidence, completely, that one day we would be successful. One day, we will achieve our freedom. That was our vision.”

Nurul Islam

By the mid-1980s, the Arakan Rohingya Islamic Front (ARIF) had been created. Commanders and soldiers of ARIF at their base camp on the Burma/Bangladesh border.

“At that time, we had lost everything. At that time when we embarked on the jungle, all of our rights and freedoms had been taken away. We had no way to address our grievances. Not through the courts or by peaceful means. We were convinced of that at the time. We knew this was the only way. We had to fight against the oppressors.”

Nurul Islam

Late 1980s - Soldiers for the Arakan Rohingya Islamic Front (ARIF) training in the jungles along the Burma/Bangladesh border.

“At the time we were doing this, we believed, and we still believe, we were not inferior to anyone! At the same time, we believed in democracy, equality and respect to all people. This is what we maintained. But on the basis of equality within the Federal Union of Burma, we wanted to have our rights and freedom ensured. For this, this movement was the only way to do it.”

Nurul Islam

1990 - A fighter for the ARIF reads the Koran at a guerrilla encampment on the Burma/Bangladesh border.

1988 - Nationwide protests took place throughout Burma in 1988, including in Arakan. Rohingya students in Yangon took to the streets to join others in demanding democratic reforms. The protests were met by a violent military crack-down. Thousands of students went into hiding or fled the country, including Rohingya.

“When the demonstrations for democracy started in 1988, being a student, I was involved. I thought it was very necessary that if the democracy comes to the country, then all the Rohingyas will have rights as before as the indigenous people. Since the 1982 black law was adopted, although the Rohingya community was deprived of Burmese citizenship, all the ethnic communities of Burma regardless of ethnicity and race had an opportunity to protest together. We all ran together. It was a proud moment. As Rohingya, we fought for the country’s democracy in 1988 because we have full trust and evidence that we are an original community in Burma…We all fought together hand in hand and shoulder to shoulder with the aim of being able to go equally if democracy was restored.”

Mohammed S

1988 - A Burmese edition of The Working People’s Daily published in early September 1988 show student groups demonstrating in the streets of Yangon, including a group of Rohingya (left side of photograph with banner). One week later government soldiers unleashed a violent military crack-down on the protestors.

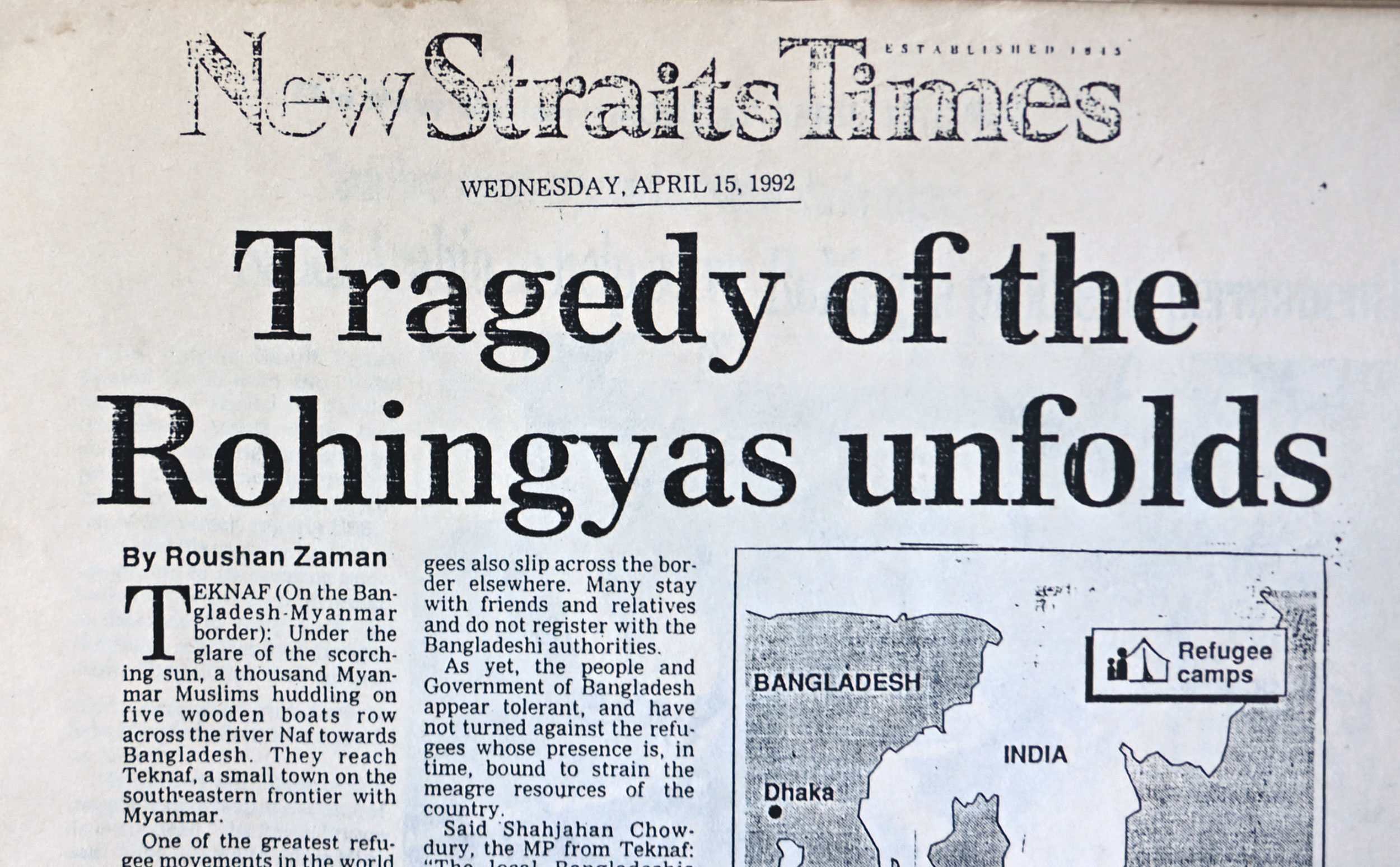

1991 - International newspapers report on the violence against the Rohingya and the flood of Rohingya refugees into Bangladesh.

1991/92 - As unrest spread throughout Burma and as political crackdowns intensified, the Burmese military increased operations against insurgency movements throughout the country. In Arakan, the military targeted Rakhine and Rohingya armed groups. In 1991, the military launched a major operation to expel so-called ‘foreigners’ in North Arakan. Operation Pyi Thaya or Operation Clean & Beautiful Nation forced over 250,000 Rohingya out of Burma into Bangladesh. The flood of Rohingya refugees out of Burma was covered widely by the international press. In late 1992 and in 1993, most Rohingya were repatriated back to Burma.

1991/92 - Rohingya in camps in southern Bangladesh after Operation Pyi Thaya.

1991 - A magazine, ARAKAN, first published by the Arakan Rohingya Islamic Front in 1991, turned its focus on the atrocities of Operation Pyi Thaya and the refugee crisis, including this issue published on October 31, 1991.

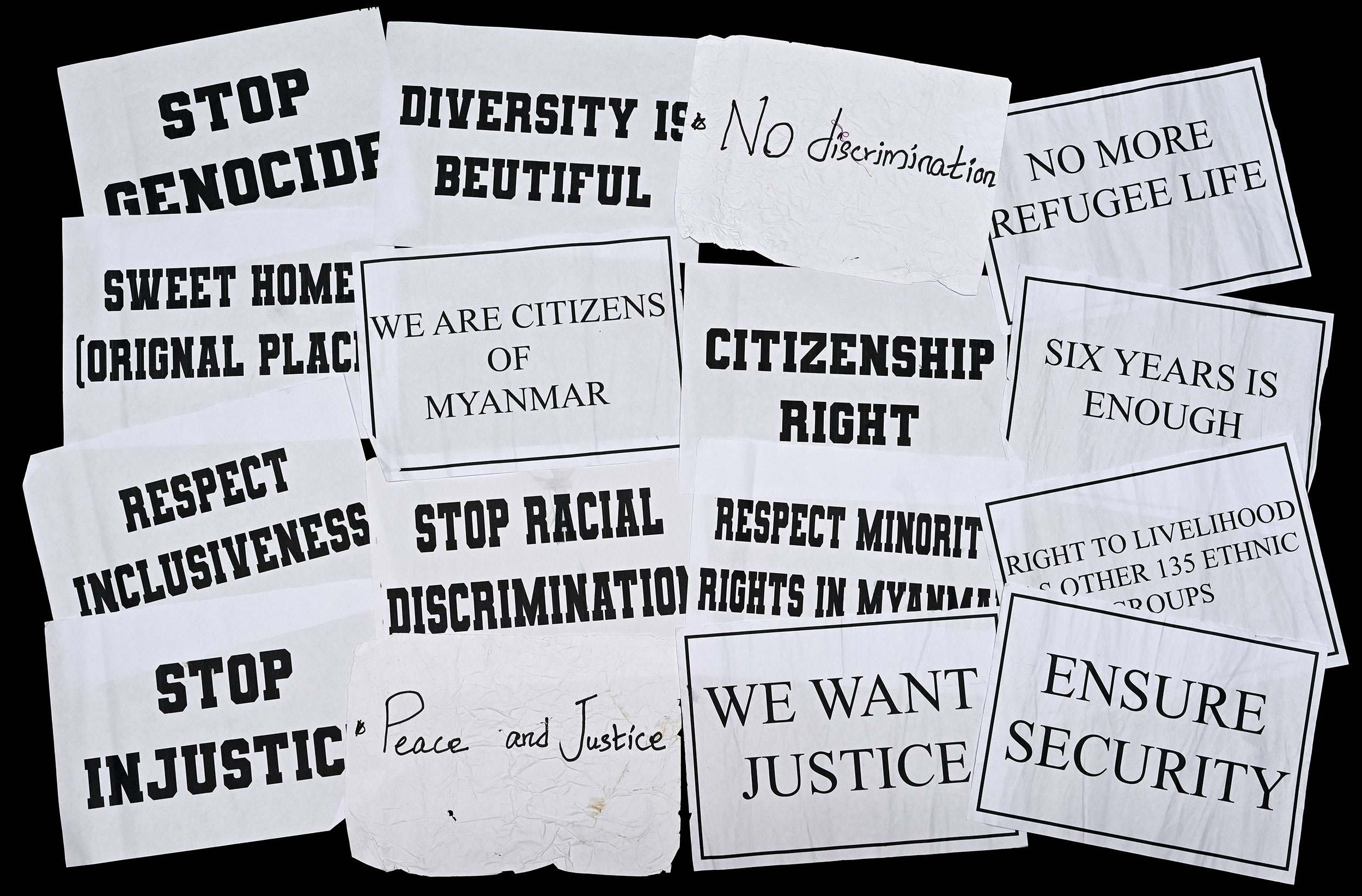

1992 - Rohingya refugees hold a demonstration in central Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh.

A transparency of a border security outpost in Maungdaw North during the 1990s.

Beginning in the early 1990s local authorities intensified their efforts to harass, restrict Rohingya movement and oppress the Rohingya in almost every aspect of daily life. A special border security force was established, called NaSaKa. Located throughout Rakhine state, NaSaKa became one of the main perpetrators of human rights violations against the Rohingya.

Mass violence continued against the Rohingya. In 2012, violence throughout Rakhine State segregated the Rohingya community from the Rakhine community and forcibly displaced over 100,000 Rohingya into internment camps. In 2016 and 2017, ‘clearance operations’ from the Tatmadaw killed thousands of Rohingya and destroyed hundreds of Rohingya villages throughout Rakhine State. Over 700,000 Rohingya fled the violence and have since lived in camps in Bangladesh. Rights groups and governments around the world have recognized the violence of 2016 and 2017 as genocide.

To commemorate the genocide of 2017, Rohingya in the refugee camps in Bangladesh create signs demanding the restoration of their rights and citizenship in Myanmar and seek justice for all minorities in the country. This is a selection of signs created by Rohingya on August 25, 2023 to mark the sixth anniversary of the genocide.