4

A New Nation

Independence and the creation of the Union of Burma

“It is well known to you that the Burmans do not want the Musalmans in Burma. Several time they tried to drive us out of Burma by force…the common trouble of all our people from highest to the lowest is the aggression of the Burmans.”

Waji Ullah

Ex “V” Force Interpreter

March 23, 1946

Personal letter to Capt. Anthony Irwin

A century of racialized British colonial policies followed by the communal violence during the war created deep divisions in Arakan. These divisions were intensified throughout the national struggle for Burma’s independence from Britain. Immediately after the war, insurgencies and chaos spread across Burma, including Arakan. Ethnic interests increasingly shaped the politics of the country. Yet, as the interim Burmese government, led by Aung San, and representatives from Burma’s larger ethnic minorities held political negotiations over equality and ‘autonomy’ prior to independence, the communities of Arakan were neglected and left out of all discussions. Rohingya and Rakhine Buddhists in Arakan immediately took action to secure their own agendas, which resulted in competing demands and opposing political alliances.

Rohingya in Arakan demanded to be seen and recognized as a people from and belonging to Burma. This ensured their representation in the elections of the Constituent Assembly in 1947, enhanced their political influence post-independence and recognized their inclusion within the collective identity of the Union of Burma. Though much larger communities throughout the country dominated the political and power dynamics, the maneuvering of Rohingya at the time ensured the Rohingya were not insignificant, especially in Arakan. Letters, records and correspondence, show the Rohingya were not passive bystanders during this crucial period in Burma’s history, rather they were active participants, staking whatever claim they could make in the new nation.

April 28, 1945

At the Elliot Hostel in Calcutta, 25-year-old Waji Ullah sat at a typewriter and wrote a short 3-paragraph letter. “It is through my wanting to go to College I am discharged from the V Force,” he wrote. Waji Ullah was a Rohingya born on December 11, 1919 in Maungdaw, North Arakan in Burma. He was a clerk and was one of the most trusted Rohingya interpreters in “V” Force. He experienced the war against the Japanese from the frontlines. Addressing himself as, ‘Ex V-Force Interpreter’, this was the first of three letters he wrote to his friend and former commanding officer from the British Army, Major Anthony S. Irwin.

June 8th, 1945

In his second letter to Irwin, Waji Ullah wrote, “It is 100 percent true saying that you are remembered by each and all in the area of Arakanese Muslim. Please send a copy of your book which is almost entirely on the doing of the Musalmans of Arakan.” He referred to Irwin’s book about ‘V’ Force in Arakan titled, Burmese Outpost. The book was recently published. Irwin wrote about Waji Ullah and several other Rohingya in the book. These first two letters (or excerpts from them) were published in the Appendix at the back of the book.

March 23, 1946

From the Baker Hostel in Calcutta, Waji Ullah wrote one more letter to Irwin. The war was over. Talk of an independent Burma was circulating and ethnic turmoil was already igniting throughout the country. As a Rohingya in 1946, he wrote about the troubles of Muslims in Burma. He wrote about Burmese independence. He wrote about his belief in freedom and the power of law.

The original letter from Waji Ullah to Anthony Irwin. March 23, 1946

“In Burma and in many other places all the people are rioting and demonstrating for freedom. But in fact I do not agree with the demonstrators and rioters. I am all for the constitution. I want the constitution to be an honest master."

Waji Ullah

March 23, 1946

Personal letter to Capt. Anthony Irwin

In 1946, General Aung San and a delegation of other leaders met in Akyab to discuss the future of Arakan and an independent Burma. This included U Nu, who would become the first Prime Minister of Burma and Rohingya leader M.A. Gaffar from Buthidaung (second on right).

“If freedom will come it will come constitutionally. It is right to ask for freedom; but to do the right thing in the wrong way is equally wrong.”

In this report submitted to the Governor of Burma in early 1947, the Advisor on Indian Affairs makes the recommendation to group together anyone who spoke one of the six recognized Indian languages, including Urdu and Bengali, into one political minority. It was suggested, this new political minority in Burma be named, the ‘National Indian Minority’ of Burma.

Many Muslim and Hindu communities, like the Rohingya, had lived in Burma for generations, long before the British colonized Burma. Regardless, discrimination and prejudice was embedded in the term ‘Indian’ as well as the accusation of being a ‘foreigner’. The recommended categorization of ‘Indian’ would influence voter registration and political representation. It would also require one to submit written claims before being included as a registered voter in the upcoming general election for the Constituent Assembly.

Minority - Classification thereof.

I suggest:

a) THAT THE INDIAN CITIZENS OF BURMA, SHALL BE GROUPED UNDER ONE POLITICAL MINORITY, CALLED

b) THAT SUCH MINORITY SHALL HAVE THE SIX INDIAN LANGUAGES ALREADY RECOGNIZED BY THE EDUCATIONAL CODES OF BURMA, WHEN BURMA WAS A PROVINCE OF INDIA, AND WHEN BURMA WAS A SEPARATE POLITICAL ENTITY

- TAMIL, URDU, TELEGU, HINDI, GUJERATI AN BENGALI -

Report submitted to Governor of Burma by

Mr. S.A.S Tyabji (Advisor on Indian Affairs)

February 22, 1947

At the same time of the release of this report, Rohingya from Maungdaw and Buthidaung gathered for a mass meeting in Maungdaw. They considered their community to be indigenous to Burma like others and protested being categorized as ‘Indians’.

The Rohingya at the mass meeting claimed this to be a ‘gross injustice’ and demanded to be recognized as ‘Burman’ or people belonging to Burma, not ‘Indians’ or ‘foreigners’. The mass meeting was led by Rohingya leader M.A. Gaffar.

Here is an original cable telegraph informing the Secretary of State of Burma in London of this meeting and the demands of the Rohingya attending the meeting. Chairman of the mass meeting: Abdul Ghaffar, Feb 19, 1947.

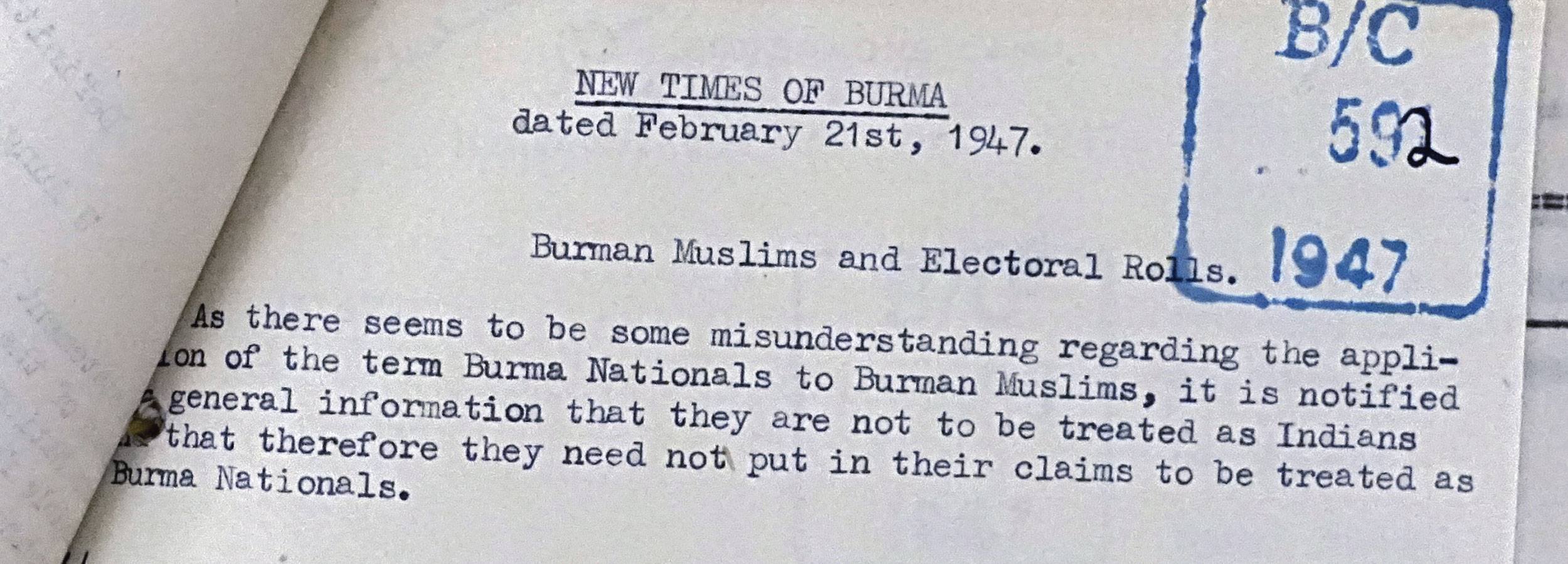

Two days after this mass meeting, the New Times of Burma reports that Burma Muslims, like the Rohingya, are not to be ‘treated as Indians’.

Election results for the 1947 Constituent Assembly, including Rohingya community leaders, Sultan Ahmed and Abdul Ghaffar. A photo of Sultan Ahmed.

Unknown: Photo Sultan Ahmed

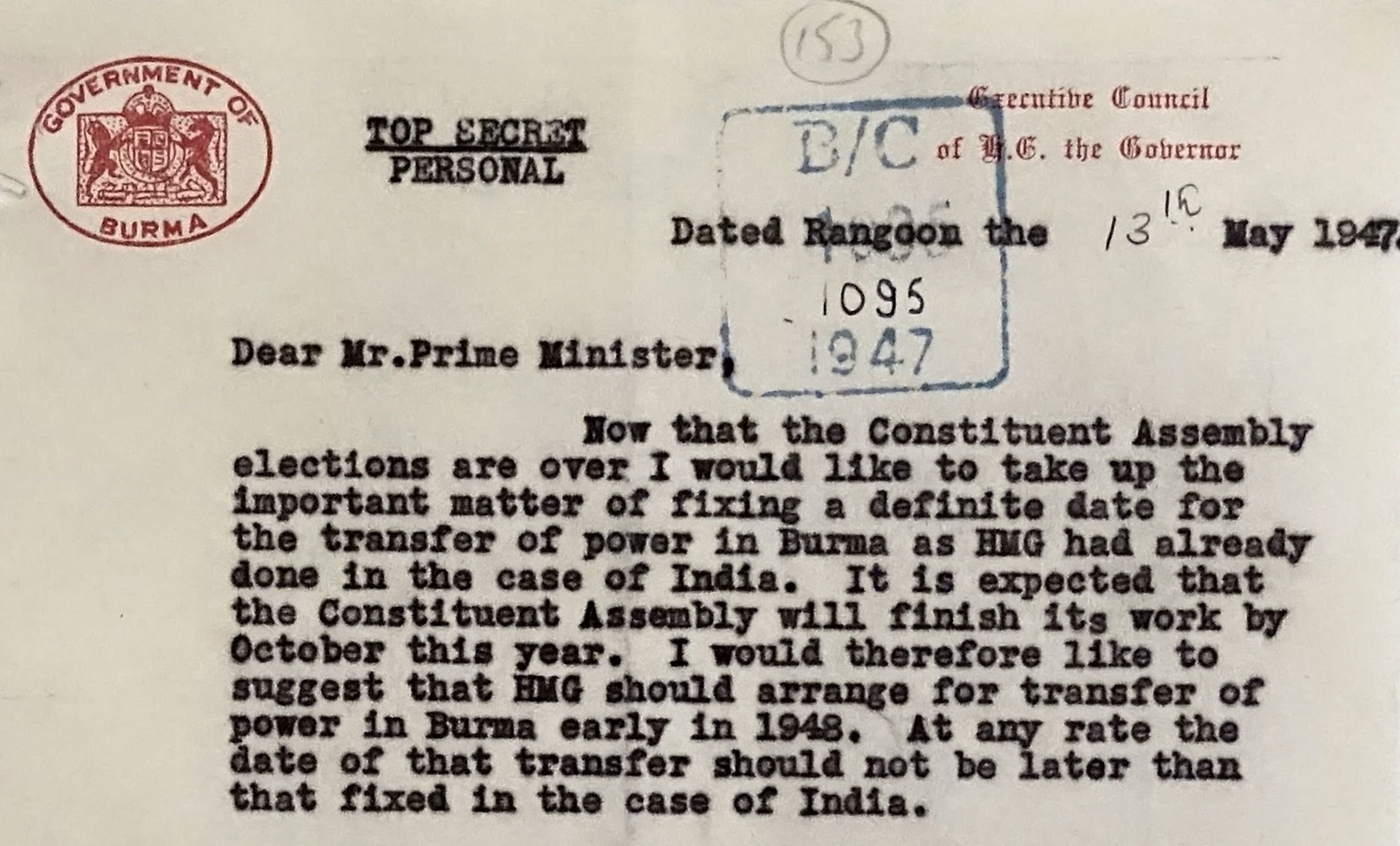

On May 13, 1947, the same day as the formal confirmation of Sultan Ahmed and M.A. Gaffar being elected to the Constituent Assembly, Aung San wrote a letter to the British Prime Minister, Clement Atlee asking for a date to be set for the transfer of power in Burma. In June 1947, the Constituent Assembly would meet for the first time.

The Constituent Assembly opened in June 1947. It was tasked with the creation of Burma’s first Constitution. A photograph of members of the Constituent Assembly from the New Times of Burma, June 20, 1947.

(3) Fundamental Rights:

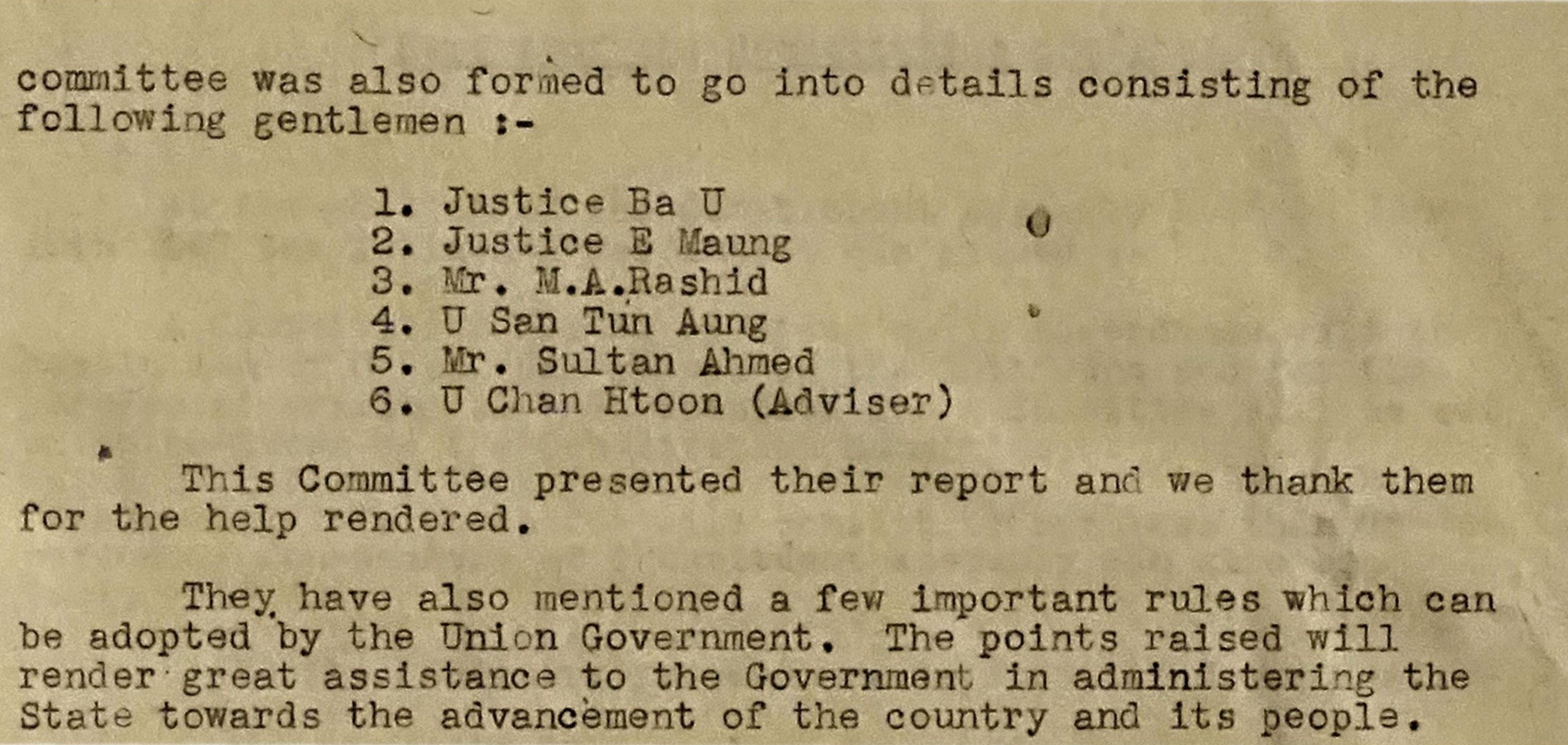

The most important point as regards the Fundamental Rights is citizenship. This point had been considered many times by the Fundamental Rights Sub Committee to come to a concrete decision. A small interim committee was also formed to go into details...

Citizenship was the ‘most important’ issue related to Fundamental Rights in the new Constitution. A special interim committee was formed to discuss how citizenship would be addressed in the drafts of the constitution. One of the six people in this committee was Sultan Ahmed.

A timeline of titles from articles published in the Burmese Review: from the approval of the Constitution in September 1947 until after Burma’s independence on January 4, 1948.

Background: Rangoon Daily, January 4, 1948

On January 4, 1948, Burma became a new and independent nation. The Fundamental Rights section of the first Constitution defined Burmese citizenship. Waji Ullah, Zain Uddin, Sultan Ahmed, M.A. Gaffar and thousands of others from the Rohingya community were recognized as citizens of the Union of Burma.

“Rohingya had the same citizenship as Aung San did. We all were citizens of Burma, same as U Nu and the first President of Myanmar, Sao Shwe Thaik. They were entitled to the same citizenship as we were.”

Aman Ullah (Rohingya elder)

2023